Pontos will Die when the Sun Rises in the West

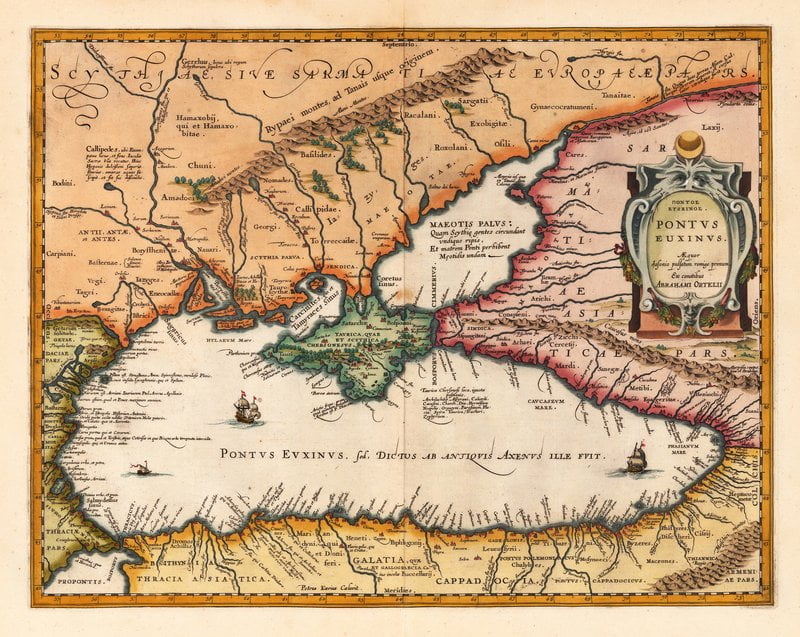

What follows is a story about the uprooting of Greeks from their ancestral homeland in Pontos, the Black Sea coastal region. Greeks began trading here in about 1,000 BC, with the first permanent settlements being established some 200 years later. So this region was as much a part of the Greek world as mainland Greece, until the events of the early 20th century.

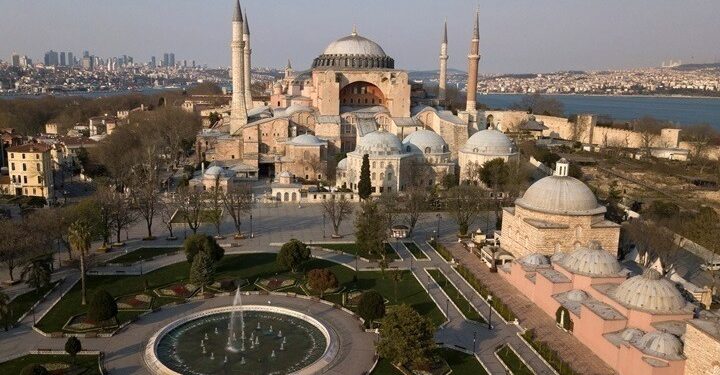

The collapse of the Ottoman Empire saw the rise of the nationalist Young Turks, but also the Balkan Wars. Then came World War I. The Treaty of Lausanne (1923) arranged for an exchange of populations between Greece and Turkey. This could hardly have come at a worse time. In other circumstances, many Pontic Greeks would have gone to other Greek settlements- in the Crimea, for example- but the October Revolution in Russia and the established of new nation states elsewhere made this virtually impossible.

The vast majority (including Saints Arsenios and Paisios from Asia Minor) therefore made their way to mainland Greece, placing an almost intolerable burden on the young state’s limited resources. That it was able to absorb such large numbers of refugees at all was due largely to the generosity of the Church, particularly the monasteries of Mount Athos, which made large areas of land available to them.

One such is the neighborhood outside Thessaloniki where I now live, which is how I was able to discover the identity of the Pontic dishes mentioned in the story [W. J. L].

‘Through the prayers of our holy fathers , Lord Jesus Christ our God, have mercy upon us and save us. Amen’.

We left the church as quietly as we could, went into the forecourt and started playing as we waited for our parents. We were enjoying ourselves and having fun, our shouts resounding all over the yard, until the priest came out with our grandfather. Our parents had taught us from an early age to respect our elders and the priests. So we stopped playing immediately and ran to get the priest’s blessing.

‘Your blessing, father’.

‘The blessing of the Lord, children. You’re blessed in having the grandfather you’ve got’.

I agree with the last part absolutely. I’m really proud of my grandpa and I’m named after him. Unfortunately for us children, however, he hasn’t yet told us the whole of his story, because he thinks we’re still too small. No matter how much I’ve tried to persuade him that a fifth grader isn’t really that little any more, I’ve always met with the same staunch resistance: ‘Alexander, you and the others need to grow a bit more yet’.

It was his name day- and mine- and he’d promised that he’d finally unlock for us the box of his recollections from his early childhood. That’s the reason we were impatient to get home.

When we did, there was a festal meal waiting for us in the yard, prepared by my grandma and my mother, with the help of all the girls in the family. On the table there were all kinds of Pontic specialties: kiltiritsia (meat-balls with bulgur wheat in tomato sauce), varenika (ravioli), sarmadhes (stuffed cabbage leaves), manti (stuffed dumplings), tsokalik (strained yoghurt), perek (cheese pie), hapsopilafon (whitebait and rice), yaglia (cheese in a bread boat), tsortan (cottage cheese), tsirikhta (doughnuts), felia (eggy bread) and otia (‘ears’, a sweet pastry). As the senior member of the household, grandfather said the prayer and we started eating. For the first ten minutes, silence reigned while we devoured the tasty food, in an effort to be done with eating as soon as possible so that we could listen to grandpa’s story.

‘Well, now that you’ve finished, I think the time’s come for me to tell you about my homeland. I think you’re old enough to understand what I’ll tell you and to draw some conclusions that’ll be useful for you in life’.

He didn’t need to tell us again. We’d all arranged ourselves comfortably on the benches underneath the plane tree and we were hanging on his every word.

‘Well, kids, I was born in Argyroupoli, a rich city with a special kind of beauty in those days, as were all the towns in Pontos before 1919. My parents were devout Christians and they made sure that the same devotion was passed on to us children. My mother, in particular, taught us about fasting on Wednesdays and Fridays, to pray, to love Christ, His mother, Our All-Holy Lady and the saints. Really, we owe them so much! At that time we were very well-off. Most of our relations, as well as my father, who was a foreman metallurgist, worked in the mines in the region, which had been run by Greeks since the 16th century. We also held a large piece of land, and were helped by Metin, a good-hearted Turk. Don’t be surprised. We got on very well with ordinary Turks. We all lived together, each one keeping their own customs and habits, without any quarreling. You could see it from the children, even. We all played together, without problems and we never excluded anybody from our gang because he was a Turk. My childhood friends went to school with me in Argyroupolis. We were united, affectionate and happy. At that time, at the beginning of the 20th century, we were living in the golden age of the Greeks of Pontos. Financially and culturally we were flourishing. Just imagine, we Greeks held the reins of commerce and industry in the Ottoman empire, because the Turks weren’t particularly well educated.

My grandfather was devoted to the Church; in fact he often went to the Monastery of Our Lady of Soumela [‘on the black mountain’ in the Pontiac dialect WJL], the Patroness of Pontos, and he took provisions for the monks, because we were so wealthy. This service was later rewarded by our Lady in an unexpected way.

But let’s take things in order. In 1908, the Young Turks revolted and sidelined the sultan. At the beginning, we weren’t afraid, because we thought they’d make a few reforms to extend the life of the declining Ottoman empire. When we discovered how badly we’d been fooled, it was too late. Whispers spread that they were determined to eliminate the Greeks and Armenians in Turkey from the face of the earth. Of course, once we went outside and started playing, we completely forgot what we’d half-heard about Turkish ethnic cleansing.

One day, my father and grandfather had gone to venerate the icons and relics at Our Lady of Soumela and to take the usual supplies to the monks.

When they returned, they seemed very upset. Elder Amvrosios told my grandfather in confidence that he’d seen Our Lady in a vision, wearing black and lamenting. And in fact, shortly afterwards, in 1916, the genocide of the Armenians was carried out. As I’ve said, until then we lived peacefully and many of our friends were Turks or Armenians. This is why we lamented the loss of so many of them so grievously. My grandfather told my father: ‘Son, gather whatever you can and get yourself to Thessaloniki, to my sister Evdokia. When you hear that things have calmed down, you can come back’. He said this because of his long years of experience and as if he foresaw what was going to happen to us. But my father absolutely refused to leave what was our homeland. ‘No way, Dad’, he said. “Haven’t we been living with Turks for all these years? They’re not going to attack us now. They need us. We hold the economy of the country in our hands. It’s a storm in a teacup’. My father couldn’t accept that so many years of living peacefully with the Turks would end in such a horrible and brutal way.

Unfortunately, my grandpa’s forebodings came true not long afterwards. On 20 May 1919, my father came home in a panic, at a time when normally he’d have been at work. He was holding a newspaper in his hand and waving it about, as if it heralded a catastrophe. That day my siblings and I were all ill with mumps and hadn’t gone to school, so we saw the whole thing. The only person who dared speak to my father was my mother:

‘What’s the matter, Yorgos. Why are you back so early?’

‘Bundle some things up, whatever you think we’ll need most, and get ready to leave. I’ve just heard that yesterday the leader of the Young Turks, Kemal [Ataturk] disembarked at Samsun with his army and the first thing he did was to meet with Topal Osman, the captain of the irregulars, those shameless robbers. Things are worse than we could ever have imagined. I wish I’d listened to you, Dad’.

My father explained everything all at once, but as he ended, his voice sounded strange. He’d only just realized what a terrible mistake he’d made and what the consequences might be for his family. But he didn’t give in. Even at the last moment he was trying to find a way to get us safely away. I imagined that the first things my mother would want to take away with us would be food and clothing, but I was completely wrong. My family’s faith was so strong that it overcame even the instinct for self-preservation. So the first thing we did was collect the icons and the relics we had in the icon-stand. It was only then that each of us took what we needed and could carry on our backs. Finally, our mother sewed into our clothes the gold coins we’d had hidden away in a trunk. We were all making feverish preparations to leave, except for our grandfather.

‘Dad, why aren’t you getting ready? Aren’t you coming?’

‘I’m too old, son. I’d never make it. I’ll go to Our Lady at Soumela and may God’s will be done’.

***

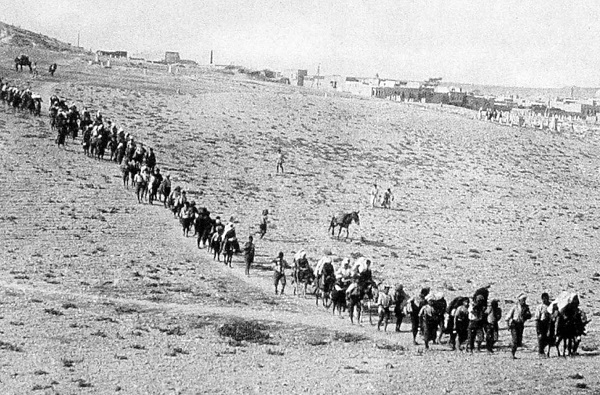

No matter how hard my parents tried to persuade him, it proved impossible. With a heart full of sorrow, my father left to warn his uncles. By nightfall, the whole family was sitting in our cart and we started out towards Trebizond. We travelled as fast as we could by night and hid during the day in thick forests. Through God’s help, we managed to get to the outer parts of Trebizond without anything untoward happening.

My father knew a few skippers there who were Greek. He entreated them to let us on their boats, but they had no room and were, in any case, ready to sail for the Crimea. He had no choice but to turn to Turkish skippers. As soon as they saw him, before he even spoke to them, they told him that they weren’t planning on sailing anywhere before the next week. In such a short time, the fanaticism and propaganda of the Young Turks had turned the affections of the Turks against us. My father realized that they were blackmailing him in order to exploit our position. He immediately offered to pay most of our gold coins to a Turk, who agreed to embark half the family onto his leaky tub, with extra payment for every other person who wanted to travel. Since we had no choice, we agreed to the horrible transaction, which cost us a fortune. But you don’t think of money in times like that. Our only thought was to get out alive, since our heads didn’t feel very secure on our shoulders. Two of my uncles, who had fewer children, got onto another Turkish boat but it cost them twice as much as we’d paid. Because of our situation, the Turkish skippers got more than they’d earned over years of work.

When they returned, they seemed very upset. Elder Amvrosios told my grandfather in confidence that he’d seen Our Lady in a vision, wearing black and lamenting. And in fact, shortly afterwards, in 1916, the genocide of the Armenians was carried out. As I’ve said, until then we lived peacefully and many of our friends were Turks or Armenians. This is why we lamented the loss of so many of them so grievously. My grandfather told my father: ‘Son, gather whatever you can and get yourself to Thessaloniki, to my sister Evdokia. When you hear that things have calmed down, you can come back’. He said this because of his long years of experience and as if he foresaw what was going to happen to us. But my father absolutely refused to leave what was our homeland. ‘No way, Dad’, he said. “Haven’t we been living with Turks for all these years? They’re not going to attack us now. They need us. We hold the economy of the country in our hands. It’s a storm in a teacup’. My father couldn’t accept that so many years of living peacefully with the Turks would end in such a horrible and brutal way.

Unfortunately, my grandpa’s forebodings came true not long afterwards. On 20 May 1919, my father came home in a panic, at a time when normally he’d have been at work. He was holding a newspaper in his hand and waving it about, as if it heralded a catastrophe. That day my siblings and I were all ill with mumps and hadn’t gone to school, so we saw the whole thing. The only person who dared speak to my father was my mother:

‘What’s the matter, Yorgos. Why are you back so early?’

‘Bundle some things up, whatever you think we’ll need most, and get ready to leave. I’ve just heard that yesterday the leader of the Young Turks, Kemal [Ataturk] disembarked at Samsun with his army and the first thing he did was to meet with Topal Osman, the captain of the irregulars, those shameless robbers. Things are worse than we could ever have imagined. I wish I’d listened to you, Dad’.

My father explained everything all at once, but as he ended, his voice sounded strange. He’d only just realized what a terrible mistake he’d made and what the consequences might be for his family. But he didn’t give in. Even at the last moment he was trying to find a way to get us safely away. I imagined that the first things my mother would want to take away with us would be food and clothing, but I was completely wrong. My family’s faith was so strong that it overcame even the instinct for self-preservation. So the first thing we did was collect the icons and the relics we had in the icon-stand. It was only then that each of us took what we needed and could carry on our backs. Finally, our mother sewed into our clothes the gold coins we’d had hidden away in a trunk. We were all making feverish preparations to leave, except for our grandfather.

‘Dad, why aren’t you getting ready? Aren’t you coming?’

‘I’m too old, son. I’d never make it. I’ll go to Our Lady at Soumela and may God’s will be done’.

***

No matter how hard my parents tried to persuade him, it proved impossible. With a heart full of sorrow, my father left to warn his uncles. By nightfall, the whole family was sitting in our cart and we started out towards Trebizond. We travelled as fast as we could by night and hid during the day in thick forests. Through God’s help, we managed to get to the outer parts of Trebizond without anything untoward happening.

My father knew a few skippers there who were Greek. He entreated them to let us on their boats, but they had no room and were, in any case, ready to sail for the Crimea. He had no choice but to turn to Turkish skippers. As soon as they saw him, before he even spoke to them, they told him that they weren’t planning on sailing anywhere before the next week. In such a short time, the fanaticism and propaganda of the Young Turks had turned the affections of the Turks against us. My father realized that they were blackmailing him in order to exploit our position. He immediately offered to pay most of our gold coins to a Turk, who agreed to embark half the family onto his leaky tub, with extra payment for every other person who wanted to travel. Since we had no choice, we agreed to the horrible transaction, which cost us a fortune. But you don’t think of money in times like that. Our only thought was to get out alive, since our heads didn’t feel very secure on our shoulders. Two of my uncles, who had fewer children, got onto another Turkish boat but it cost them twice as much as we’d paid. Because of our situation, the Turkish skippers got more than they’d earned over years of work.

When they returned, they seemed very upset. Elder Amvrosios told my grandfather in confidence that he’d seen Our Lady in a vision, wearing black and lamenting. And in fact, shortly afterwards, in 1916, the genocide of the Armenians was carried out. As I’ve said, until then we lived peacefully and many of our friends were Turks or Armenians. This is why we lamented the loss of so many of them so grievously. My grandfather told my father: ‘Son, gather whatever you can and get yourself to Thessaloniki, to my sister Evdokia. When you hear that things have calmed down, you can come back’. He said this because of his long years of experience and as if he foresaw what was going to happen to us. But my father absolutely refused to leave what was our homeland. ‘No way, Dad’, he said. “Haven’t we been living with Turks for all these years? They’re not going to attack us now. They need us. We hold the economy of the country in our hands. It’s a storm in a teacup’. My father couldn’t accept that so many years of living peacefully with the Turks would end in such a horrible and brutal way.

Unfortunately, my grandpa’s forebodings came true not long afterwards. On 20 May 1919, my father came home in a panic, at a time when normally he’d have been at work. He was holding a newspaper in his hand and waving it about, as if it heralded a catastrophe. That day my siblings and I were all ill with mumps and hadn’t gone to school, so we saw the whole thing. The only person who dared speak to my father was my mother:

‘What’s the matter, Yorgos. Why are you back so early?’

‘Bundle some things up, whatever you think we’ll need most, and get ready to leave. I’ve just heard that yesterday the leader of the Young Turks, Kemal [Ataturk] disembarked at Samsun with his army and the first thing he did was to meet with Topal Osman, the captain of the irregulars, those shameless robbers. Things are worse than we could ever have imagined. I wish I’d listened to you, Dad’.

My father explained everything all at once, but as he ended, his voice sounded strange. He’d only just realized what a terrible mistake he’d made and what the consequences might be for his family. But he didn’t give in. Even at the last moment he was trying to find a way to get us safely away. I imagined that the first things my mother would want to take away with us would be food and clothing, but I was completely wrong. My family’s faith was so strong that it overcame even the instinct for self-preservation. So the first thing we did was collect the icons and the relics we had in the icon-stand. It was only then that each of us took what we needed and could carry on our backs. Finally, our mother sewed into our clothes the gold coins we’d had hidden away in a trunk. We were all making feverish preparations to leave, except for our grandfather.

‘Dad, why aren’t you getting ready? Aren’t you coming?’

‘I’m too old, son. I’d never make it. I’ll go to Our Lady at Soumela and may God’s will be done’.

***

No matter how hard my parents tried to persuade him, it proved impossible. With a heart full of sorrow, my father left to warn his uncles. By nightfall, the whole family was sitting in our cart and we started out towards Trebizond. We travelled as fast as we could by night and hid during the day in thick forests. Through God’s help, we managed to get to the outer parts of Trebizond without anything untoward happening.

My father knew a few skippers there who were Greek. He entreated them to let us on their boats, but they had no room and were, in any case, ready to sail for the Crimea. He had no choice but to turn to Turkish skippers. As soon as they saw him, before he even spoke to them, they told him that they weren’t planning on sailing anywhere before the next week. In such a short time, the fanaticism and propaganda of the Young Turks had turned the affections of the Turks against us. My father realized that they were blackmailing him in order to exploit our position. He immediately offered to pay most of our gold coins to a Turk, who agreed to embark half the family onto his leaky tub, with extra payment for every other person who wanted to travel. Since we had no choice, we agreed to the horrible transaction, which cost us a fortune. But you don’t think of money in times like that. Our only thought was to get out alive, since our heads didn’t feel very secure on our shoulders. Two of my uncles, who had fewer children, got onto another Turkish boat but it cost them twice as much as we’d paid. Because of our situation, the Turkish skippers got more than they’d earned over years of work.

Source: pemptousia.com