The Fall of Constantinople, 1453: Part 2

The union with the Catholics was overwhelmingly rejected by the population of Constantinople and was interpreted as engendering divine disfavour. In 1443 the emperor John made his brother Constantine XI Dragaš Palaiologos Despot of Mistra in the Peloponnese, where Plethon later died. Constantine managed to re-conquer swathes of territory from the Ottomans leading up to the Hexamilion at the gulf of Corinth, taking advantage of a crusade launched by the Poles, Transylvanians and Burgundians, which, as it went through Orthodox territories forced Latin or Catholic practices upon Orthodox Christians with violence. This crusade was defeated by Murad at Varna, upon which Constantine Palaiologos pushed his armies beyond the gulf of Corinth to invade central Greece. This was to prove a terrible overreach, as Murad discovered his plans and drove the Byzantines back into the Peloponnese, into the Morea. In 1448, the emperor John died and Constantine was invested and acclaimed Byzantine emperor at Mistra.

Like his brother, Constantine once again turned westward for help. The Venetians, Genoese, Burgundians and others were sympathetic, but the Pope insisted that the Orthodox unequivocally accept union with Rome – under the parameters set by Rome – before they could send any help. The Grand Duke Lukas Notaras summed up the opinion of most of the clergy and the laity in Constantinople in this period: “Better the Sultan’s turban than the Pope’s cap.” The Pope then sent Isidore of Kiev, who was with the Orthodox at the council of Ferrara-Florence in 1438-49 and now a Roman cardinal, to Constantinople with 500 archers, which encouraged the Byzantines and Constantine, after avoiding the prospect of union for most of his life, accepted to come under the Catholics. A uniate liturgy then was held in Hagia Sophia, with Michael Doukas (d. 1462) writing that the emperor was just pretending to go under Rome. Nevertheless, the union was not accepted by the populace, and Gennadios Scholarios, who since returning from the council of Ferrara-Florence had become a monk, wrote on his door before disappearing – for now – from public life: “O unhappy Romans, why have you forsaken the truth? Why did you not trust in God, instead of the Italians? In losing your faith you will lose your city.”

In January 1453, further Western help did arrive in Constantinople, but it was not sent via the papacy. A wealthy Genoese ‘soldier of fortune’ named Giovanni Giustiniani Longo arrived in the City with seven hundred soldiers paid for at his own expense. He became the main defender of the landward walls when the final siege took place. In the spring of that same year – Mehmet’s forces, between 60 and 80,000 strong, marched from Edirne towards Constantinople, and on April 11 the Ottomans attacked the City walls with canon-fire. The bombardment continued for a day and a night. In mid-April, an attack on the landward walls was thwarted by the Romans and the Genoese working in concert, compelling Mehmet to turn to a naval strategy. On 18th of April the Sultan ordered Baltoglu, the admiral of his fleet, to take the Golden Horn, the thin body of water to the northern side of the Constantinopolitan peninsula separating the promontory from Pera or Galata. They were defeated, and four Genoese trading ships with supplies for the city managed to make it into the Horn.

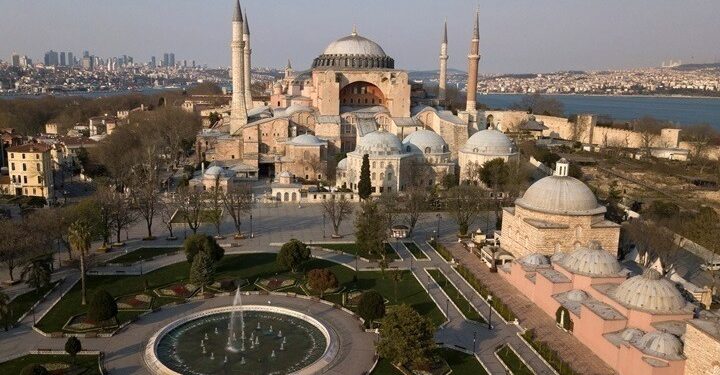

At this point, Mehmet realised that he had to get around the big chain cordoning off the Golden Horn. His workers created wooden rollers greased with fat to run from the shore of the Bosphorus, around Galata, and to the Horn. On 22nd of April his entire fleet, sixty-seven vessels, was in the Golden Horn, facing the northward walls of the city. On 16th of May, on the landward side of the City, sappers were creating underground trenches to reach the outer walls, but these were discovered and destroyed by the Byzantines. On 19th of May, a Turkish siege tower was repelled. Indeed, this series of small victories by the city’s defenders were overshadowed by terrible portents. On 22nd of May the moon was eclipsed, and on the following day at midday the icon of the Mother of God Hodegetria—“She who leads the way”—was processed around the City for the latter’s protection, but a terrible thunderstorm broke out and the icon slipped and fell from the frame on which it was held; the procession was then immediately abandoned. On the 24th of May the city was enveloped by a thick fog until the evening, when a red glow was seen on the dome of Holy Wisdom (Hagia Sophia)—the main cathedral of the city and the largest in Christendom at the time—a glow which rose to the peak of the dome, and then disappeared.

These omens were interpreted by the Byzantines as further signs of God’s disfavour, yet despite this, on 28th of May, Roman Catholics and Orthodox celebrated a liturgy together in Hagia Sophia. The emperor took holy communion, fell to his knees and begged God for forgiveness, and left the church. In the early hours of the 29th of May, the final siege began. At 1:30am the Turkish canon bombardment began at the St Romanos Gate. The Sultan sent his irregular troops to attack the landward walls, but they were cut down by the Byzantines, and after two-and-a-half hours of slaughter, Mehmet called them back. At 4am, a second wave of troops, an Anatolian army – many of whom were former Christians – attacked but was also repelled. At 5am the third wave, Janissaries made up of former Christian boys converted to Islam and trained as the Sultan’s elite guard, was sent to attack. The emperor Constantine led the defence which seemed to be holding ground, until two things that changed the course of the battle happened: a small gate near the Blachernae district and close to the Golden Horn, called the kerkoporta or ‘Wooden Gate,’ was used by the Bocchiardi brothers from Genoa for small skirmishes. In the heat of battle, they forgot to lock it when returning from a skirmish. Soon fifty Ottoman soldiers entered this gate and raised the Ottoman banner on the ramparts.

This of course gave enthusiasm to the Ottomans. The Genoese captain Giustiniani Longo was injured while defending the area near the St Romanos gate. It was the second time he was injured in two days. He asked the emperor for the keys to the gate to re-enter the city; Constantine reluctantly obliged, but when the Genoese saw their master being carried out they though they were retreating and ran to follow him, leaving the Romans to fight on their own. Constantine XI Palaiologos was last seen alive near the St Romanos gate, where the fighting was thickest. The city was then taken, and the last emperor of Constantinople passed into legend as ‘the Marble King.’

By Mario Baghos

Dr Mario Baghos is Lecturer in Patristics and Church History at St Andrew’s Greek Orthodox Theological College, and Chief Publishing Officer of St Andrew’s Orthodox Press. His most recent book is entitled From the Ancient Near East to Christian Byzantium: Kings, Symbols, and Cities (Cambridge Scholars Publishing, 2021). He contributes weekly articles to a series on the English VEMA website on the history and symbolism of existing Byzantine monuments and churches in Constantinople, entitled ‘Remnants of New Rome.’