The letter that spurred the restoration of a historic monastery

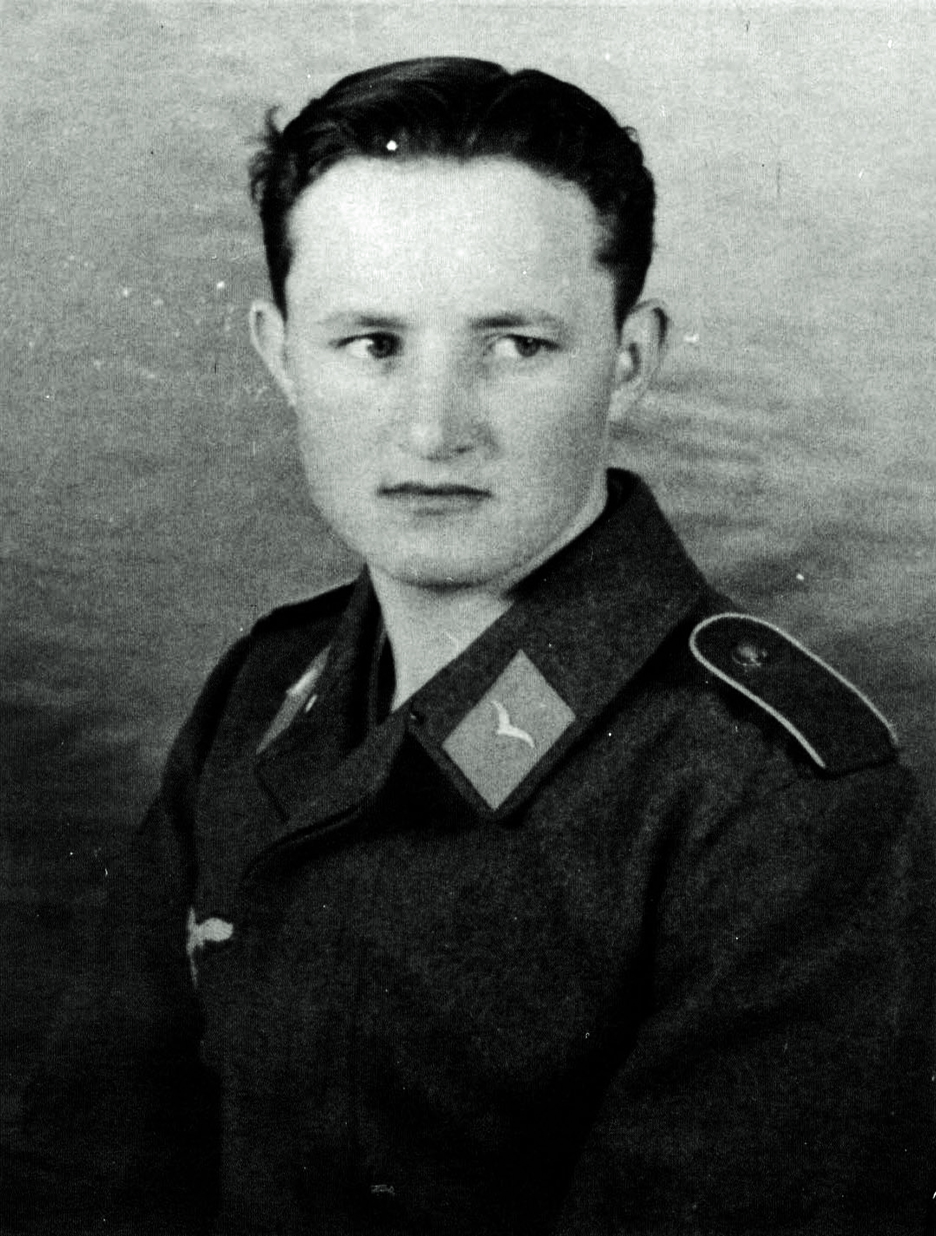

One morning in 1996 an envelope arrived by post at the Monastery of Agios Dionysios in the foothills of Mount Olympus, addressed to Abbot Maximos and naming one Karl Faber from Germany as the sender. The enclosed letter warned the monks that they were in for a surprise – and so it was.

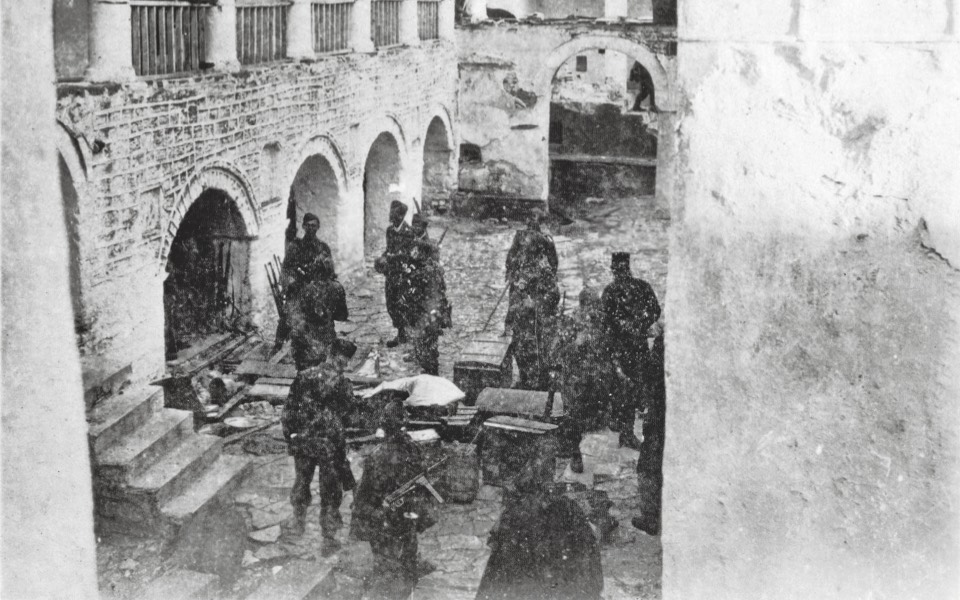

To fully understand that letter we must look back to the Nazi occupation of Greece and specifically to the fateful day of April 29, 1943, when a squad of German commandos based in Litochoro climbed 800 meters in the middle of the night carrying large quantities of explosives into the heart of Mount Olympus. They reached their destination around dawn, placed their explosives strategically around the site and demolished their target. That target was the historic Monastery of Agios Dionysios, in the Enipeas Gorge. Its 12 monks survived the blast by escaping with nothing more than the patron saint’s icon to the monastery’s glebe further downhill, where they were later arrested and interrogated.

The German commandos had been acting on intelligence, probably accurate, that Agios Dionysios was sheltering and aiding fighters in the local resistance movement. It was not the first time the monastery had supported an insurgency nor was it the first time it had been targeted for reprisals by enemy forces. Agios Dionysios had also participated in the Greek War of Independence and was pillaged by the Turks in 1821 following a three-day battle after which its abbot, Methodios, and its 12 monks were executed. It had also lent assistance during the Macedonian rebellion of 1878 and the Macedonian Struggle (1893-1908).

As in the wake of its earlier misfortunes, the monks – who now serve at the Nea Moni or New Monastery of Agios Dionysios some 3 kilometers from Litochoro – and the saint’s faithful embraced the ruins of the old monastery after it was demolished and set about its restoration, mainly relying on testimonies of what it looked like before the blast. It was no easy feat given that there were no architectural drawings to serve as a guide and the building had been completely destroyed.

‘God’s gift’

That is until that letter from Germany arrived in 1996. The monks viewed it as a “gift from God,” and it drastically bolstered the restoration effort. Accompanying the letter were photographs taken moments before the blast by one of the German soldiers. The photographer was none other than Faber himself, who sent the envelope almost half a century after the attack and shortly before he died, in the hope that – as he wrote in the letter – the photographs would aid with the restoration.

“Thanks to German’s photographs and the remnants of the building, our team of researchers was able to draw up a plan for its restoration. Very little of the original structure had survived, so these photographs were tremendously helpful,” architect Sotiris Tzimas (no relation to the writer), who is responsible for overseeing the reconstruction of one of the monastery’s bigger wings, tells Kathimerini.

“The photographs were taken into account in the restoration study because they revealed elements that were absent from other material we had,” explains Silouanos, a monk who showed us around the ruins of what was once a jewel of Byzantine ecclesiastical architecture.

Apart from his photos, Faber included the relevant parts from his diary in the envelope to the monastery, which, along with the letter, describe in detail the events that took place in the Enipeas Gorge on April 29, 1943.

Faber’s notes

In his diary, Faber wrote:

“29/4/1943: Time, 00.30 (midnight). We begin our march toward the Monastery of Agios Dionysios. It is a difficult march, through rocks and broken branches. We make visual contact with the monastery at dawn. There are machine guns on our right to cover us. I look at the monastery, more than six centuries old. On our way back, we hear the first blasts. We return to camp in the afternoon.

“I was a signals operator to Commander Strohmeier (hailing from Vienna). I heard him tell a superior officer to assume command, as he wanted to personally visit the monastery. I asked to accompany him. He agreed. I had my Leica camera in my mess kit.”

Karl Faber never returned to the scene of the crime. Perhaps he thought that mailing the photos and the letter would be some form of atonement. However, his wife and daughter visited the ruined monastery after his death in September 2003, after being invited to attend a conference on Agios Dionysios in Litochoro by Abbot Maximos.

“It is a great honor to be here among you. My late father was here 60 years ago during the war, and in 1996 he sent you a letter and some photos of the monastery before it was destroyed. My father would have been very glad to receive your invitation and we, his children, continue to be admirers of your country and your civilization,” said his daughter from the conference’s stand.The restoration, funded by the Culture Ministry and the European Union Partnership Agreement for the Development Framework (ESPA), is moving along slowly, as a faithful restoration requires a great deal of care. A legal bid to include the monastery’s restoration as part of German war reparations was not successful. When visiting the ruins, the German ambassador expressed his sympathy for the cause but stated that the issue was part of the wider “suspended” issue of war reparations.

With ‘respect’ to the original

This time of year, the home of the gods is cloaked in a white blanket of snow, with many parts being inaccessible. Steep, continuous turns on the solitary, winding road from Litochoro to the mountain’s peak make driving above a certain altitude almost impossible in the frozen depths of winter.

“You got here just in time,” Silouanos tells us on the bright and warm day of our visit.

The ruins of the Agios Dionysios Monastery appear almost out of nowhere as you turn down the fork a few hundred meters above the restaurant at Prionia into the canopied Enipeas Gorge. Until a few weeks ago, the clamor of hammers hewing stones rung out across the ravine. Now the ruins are covered in a veil of silence.

“When it rains the rocks become damp and we cannot work with them. Restoring a monastery requires respect and faithfully upholding the original architecture,” says Tzimas.

Silouanos zips around through the parts undergoing repairs, structures that feel like they will crumble at the slightest touch.

The damage inflicted on the monastery by the large amounts of TNT was devastating. The whole of Olympus was rocked by the explosions. Not even the patron saint Agios Dionysios could protect his retreat from the vindictive fury of the Nazis, nor did Zeus throw down a lightning bolt to save the Byzantine masterpiece at the heart of his realm.

Greece’s mountain monasteries were targeted during the Nazi occupation because the Germans had designated them as threats, suspecting that they sheltered and supported armed guerrillas.

Tzimas, the architect, told us that he has participated in the survey and restoration of 12 monasteries destroyed by Nazi forces during the war.

The letter

“I was 21 years old and was enlisted in a Jager Unit (light infantry) that had camped near Litochoro on April 27, 1943. A lawyer from Hamburg, a great admirer of Greece, sent me color pictures of the ruined monastery that he had taken himself. I do not have to tell you how tremendously saddened I am by the destruction of this grand and beautiful monument.

“On April 29, 1943, our unit was responsible for covering and securing the heights to the north of the monastery. We had set out from our camp at midnight and reached the heights over the monastery by dawn. I was the signal operator in communication with our unit’s commander, who was a professor from Vienna. I even heard him tell his replacement to assume command as he wanted to see the monastery himself. I always carried my Leica camera with me, storing it in my mess kit, and asked the commander if I could be allowed to accompany him. He was kind enough to allow me to take pictures.

“I am sending you four enlarged photos I took back then. These photos should allow one to capture in part what the monastery was like. I took the photos quickly because we did not have much time. Maybe these photos will be useful in the restoration of the monastery.

“I thank you from the bottom of my heart and I wish you all good health and for peace on Earth, so no other monasteries have to be destroyed.”

Source: ekathimerini.com