181 years since the passing away of Theodoros Kolokotronis, the “Elder of Moria”

On this day, 4 February 1843, the leading figure of the Revolution of 1821, Theodoros Kolokotronis, passed away. The so-called “elder of Moria” was a member of the Kolokotronai family, which since the 16th century was in constant conflict and war with the Turks.

A number of historical figures have distinguished themselves in the Greek War of Independence. Georgios Karaiskakis, Odysseas Androutsos, Markos Botsaris and Laskarina Bouboulina are some of the most famous among these personalities, but one name usually stands out: Theodoros Kolokotronis, the archetypal “hero of 1821”.

As a leading figure of the Greek Revolution, Kolokotronis, often referred to as “the Old Man of Morea (o Geros tou Moria)”, played a seminal role in the history of Modern Greece, not only in the war but also in shaping the new state, and has been associated with some of the greatest successes of the national struggle for freedom, such as the Siege of Tripolitsa and the Battle of Dervenakia.

Background: Klephts and armatoles

Following the establishment of Ottoman rule in the mainland of Greece, several were those (especially coming from the army or local militia) who chose to take refuge in the mountains and live as bandits. Throughout the Ottoman period, they would be joined by others who sought to flee vendettas, jizyah and kharāj taxes or the law. These people would eventually be called klephts (kleftes, “thieves”) as they lived by brigandage.

Due to the activity of klephts and other insurgents, the Ottomans employed irregular forces commissioned enforcing the Sultan’s authority and maintaining the peace. This type of militia, called the armatoles (armatoloi, “armed men”), which had already existed in the Byzantine Empire, were increasingly used by the Ottomans in areas with many klephts or irregular terrain. They were often manned and usually led by former notorious klephts, and many would fluctuate between the two roles.

When the Greek Revolution started being planned, these seemingly rivalling but actually interchanging groups were united, forming the nucleus of the Greek fighting forces throughout the War of Independence.

Kolokotronis and his men in their sangar, Peter von Hess, (National Gallery–ASM)

Early life

Kolokotronis was born on 3 April (O.S.) 1770 in Ramovouni of Messinia, although his family lived in Limbovisi of Arcadia, and he spent his childhood in the fortress of Kastanitsa (or Kastania) in the semi-autonomous Mani Peninsula in Morea (the Peloponnese). His father was Konstantinos Kolokotronis, a klepht leader who came from a prominent family; the presence of the Kolokotrónis family (initially with the name Tzerginis, and later Botsikas) is attested in Messinia as early as the 17th century, and its history is surrounded by many legends.

Konstantinos Kolokotronis had taken part in the ill-fated Orlov Revolt of 1770, an armed rebellion in the Peloponnese that broke out in February 1770, following the arrival of Russian Admiral Alexey Orlov, commander of the Imperial Russian Navy during the Russo-Turkish War (1768–1774), at the Mani Peninsula. His son, Theodoros, born a few days after the revolt was suppressed, was named after Fyodor Orlov, brother of Alexey. Konstantinos would eventually be killed in July 1780 at the Siege of Kastania, where the Ottomans attacked the klephts of Mani. Theodoros’s mother however managed to escape the massacre, allegedly disguised as a man, together with her children.

At the age of fifteen, Theodoros Kolokotronis went with his mother and siblings to stay in the village of Akovos in Arcadia, where his uncle lived; young Theodoros was chosen as the leader of the Kolokotronis clan, consisting of twelve men of his family and about one hundred and fifty followers. In 1790 he married the daughter of a kodjabashi in Akovos. He is said to have begun working as an armatole against the klephts of the region at the age of twenty, and would continue alternating between the roles of klepht and armatole for the next fifteen years, earning considerable fortune but also great notoriety, resulting in firmans being issued for his head more than once in the following years.

Kolokotronis puts his son under oath, Dionysios Tsokos, (National Gallery–ASM)

Move to Zakynthos and initiation to the Filiki Eteria

In February 1806, the Ottomans began a sweeping effort to eliminate the klephts of Morea; in February of that year, Theodoros’s brother Giannis “Zorbas” Kolokotronis, along with a few other members of the clan, was ambushed and killed by Ottoman soldiers Theodoros managed to escape with his wife to the Ionian Islands –then a Russian protectorate– and eventually settle in Zakynthos, where he would stay for the better part of the next fifteen years.

Following the conquest of the island by the United Kingdom, he enlisted in the British forces in 1810, and served in the 1st Regiment Greek Light Infantry (later 1st Greek Light Infantry), under Richard Church, until it was disbanded in 1816. He distinguished himself in battles against the French, and would soon reach the rank of major. Kolokotronis would in fact continue wearing his regimental helmet as a fighter of the Greek army during the War of Independence, with the personal addition of a cross on the front, creating the iconic image we now see in his most famous portrayals.

It was during his time in the Ionian Islands that Kolokotronis experienced a political and national “awakening”, through his interactions with several personalities from foreign armies and his study of Greek history. In 1818, Christos “Anagnostaras” Papageorgiou (an ex-military officer in the Imperial Russian Army in Zakynthos, and later a general in the Greek revolutionary army) initiated him into the secret revolutionary organisation Filiki Eteria (“Society of Friends”), which coordinated the launching of the Greek War of Independence against the Ottoman Empire. In 1819, Kolokotronis would meet Count Ioannis Kapodistrias –then Foreign Minister of Russia– who, at the time, remained unconvinced that a Greek revolution could be successful.

In June 1820, the Filiki Eteria appointed Kolokotronis in charge of the Peloponnesian troops, acknowledging his experience and status. In January 1821 he would permanently leave Zakynthos and return to the mainland.

Kolokotronis’s brace of engraved pistols, an ornate cavalry-style cuirass and regimental helmet, from his service in the British Army, on display at the National Historical Museum, Athens

Outbreak of the Greek War of Independence

In January 1821, Theodoros Kolokotronis would arrive in Mani, under instructions by Alexander Ypsilantis, leader of the Filiki Eteria; there he would contact Petrobey Mavromichalis, the ruler (bey) of the semi-autonomous Mani. They reached an agreement for cooperation in the upcoming revolt, marking a seminal moment of unification between the klephts and armatoles on one side and the kodjabashis (elders, chieftains) and beys of the Morea on the other – two large groups with long-standing rivalries. It was this consensus that essentially made the revolution possible.

The date of the declaration of the Greek Revolution in the mainland was set to be on 25 March 1821, not only due to the symbolism of the Feast of the Annunciation, but also because it made sense to begin a war in spring, on a date that would be easily known to all Greeks, and at a time when the movement of large groups of people could be seemingly justified by the holiday. Eventually, several local rebellions broke out on earlier dates, such as the revolt in Areopoli on 17 March and the liberation of Kalamata, by a force led by Kolokotronis and Mavromichalis themselves, on 23 March; however, the date of 25 March remains historically linked with the official declaration of the War of Independence (hence its subsequent designation as Greece’s first official national holiday).

The Greek irregular forces comprised of klepths and armatoles together with Greek civilians, most of whom were simple farmers with no experience in combat. Kolokotronis, acted as de facto commander in chief, due to his great strategic skills, as he combined his experience of guerrilla warfare from his time as a klepht with his knowledge of regular army tactics from his service in the Brittish infantry.

The Battle of Tripolitsa and the surrounding villages, c. 1836-39, Panagiotis Zographos (via Wikimedia Commons)

Siege of Tripolitsa

As the Greek Revolution started to spread, Kolokotronis prompted the Greek fighters to besiege Tripolitsa (modern day Tripoli), then a pre-eminent town in southern Greece which served as the administrative centre for Ottoman rule in the Morea (Peloponnese), due to its geostrategic position in the centre of the peninsula. The Greeks benefitted from the fact that Hurshid Pasha, governor of the Morea Eyalet, had left his seat in Tripolitsa, along with several of his men, expedition against the rebellious Ali Pasha of Yanina (in north-western Greece).

The siege of Tripolitsa started in June and lasted for nearly five months, during which the Greeks secured several important victories in the surrounding areas, such as the Battle of Valtetsi, the first decisive Greek victory in the war, where Kolokotronis’s strategic manoeuvres also played an important role; on 23 September (O.S.) the town eventually fell to the Greeks. Kolokotronis, named a supreme commander by the Provisional Administration of Greece in January 1822, would be a leading figure in other Greek successes that followed, such as the Ottoman surrender of the castle of Acrocorinth in January and the battle of Saravali in March of the same year.

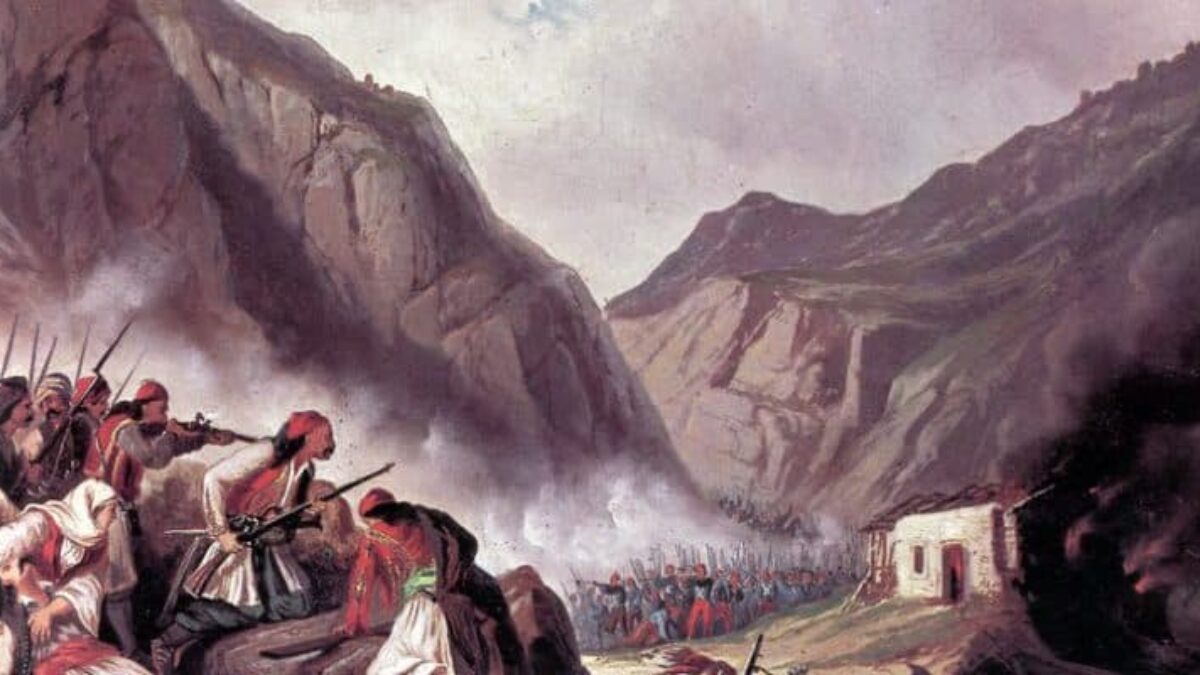

The Battle of Dervenakia, Theodoros Vryzakis, (National Gallery–ASM)

Battle of Dervenakia

In June 1822, the Ottomans launched a large military campaign led by Mahmud Dramali Pasha (hence known as the Expedition of Dramali) to quench the revolution; thousands of soldiers and cavalry set out from the city of Larissa in Thessaly to recapture Tripoli. In their advance from Central Greece towards the Morea, Dramali’s troops recaptured several positions previously held by the Greeks, spreading panic in their wake. After crossing to the Peloponnese peninsula, Dramali seized Corinth and the castle of Acrocorinth in July and decided to continue towards the cities of Argos and Nafplion, which he reached passing through a narrow gorge known as Dervenakia.

While Dramali was stationed near Argos, laying siege to the city, the Greeks under Kolokotronis assembled an army of volunteers and pursued a scorched earth policy in the areas surrounding the Argolic plain, threatening Ottoman troops with starvation, and forcing the Pasha to retreat towards Corinth, again through Dervenakia on 26-28 July (O.S.). Greek troops under leaders such as Antonis Kolokotronis (Theodoros’s cousin), Dimitris Plapoutas, Nikitaras and Papaflessas, had been strategically positioned in the narrow passes, ambushing Dramali’s army and resulting in one of the Greek forces greatest victories, masterfully planned and orchestrated by Theodoros Kolokotronis. The destruction of a large part of the Ottoman forces helped establish the revolution, which could have otherwise been quelled. After Dramali’s defeat, Nafplion, Corinth and Acrocorinth would soon surrender to the Greeks.

Kololotronis and his personal escort, c. 1828, Pierre Peytier (via Wikimedia Commons)

Civil Wars

From 1823 to 1825, the Greek War of Independence was stained by two civil wars, instigated by political, factional and regionalist interests; there was extensive disagreement on the way the war should continue to be fought and, especially, on the way the nascent Greek state should be governed.

Military leaders, headed by Kolokotronis, felt marginalised by Phanariots and political leaders such as Alexandros Mavrokordatos; these frictions led to the first civil war, while the second and more destructive one soon was caused the rift also which emerged between the Roumeliotes (inhabitants of Central Greece) and islanders, on the one hand, and Peloponnesians on the other. During that second and darkest period of the civil strife, Theodoros’s eldest son, Panos Kolokotronis, was killed in an ambush in late 1824; in February 1825, Kolokotronis surrendered to the Provisional Administration –then headed by the Hydriot ship-owner Georgios Kountouriotis– and was detained in a Hydra monastery, along with his other son, Ioannis “Gennaios” Kolokotronis (Gennaios, “Brave”).

Invasion of Ibrahim and foreign intervention

In the spring of 1825, the War of Independence faced a grim outlook; to add to the Greeks’ disunity and their dire financial situation, the Ottomans had called for reinforcements from their vassal state of Egypt. Muhammad Ali, governor of Egypt, sent a large army and fleet led by his son, the notorious Ibrahim Pasha. After landing in the Peloponnese in February 1825, Ibrahim wreaked havoc among the Greeks; by May he had reconquered a large part of the peninsula, forcing the provisional government to amnesty Kolokotronis and restore him as supreme commander of the Greek forces. But Ibrahim’s army was too large and well-organised, and would go on to conquer Tripoli, destroy Argos. In late 1825 he joined Reshid Pasha at the siege of Missolonghi in Central Greece; the town would fall to their hands in April 1826.

The Greek forces could not do much to fend off Ibrahim’s advancement, only holding onto a few strongholds and once again finding themselves on the brink of civil discordance. Finally, in the spring of 1827, they convened at the Third National Assembly and decided to call on foreign help. They appointed two illustrious Philhellenes, naval officer Lord Cochrane and Major Richard Church as supreme commanders of the navy and army, respectively. Kolokotronis, Nikitaras, Plapoutas and other prominent Greek fighters had great respect for Church, under whom they had served at the Greek Light Infantry in the Ionian Islands. The most contentious subject was the question of political leadership. Kolokotronis was among the first to propose and ardently support the appointment of Count Ioannis Kapodistrias, the most prestigious Greek of his time, as Governor, a decision which was ultimately adopted by the Assembly.

The Greek forces had however already suffered too many blows and were not efficient in regular army operations, while the administration was virtually bankrupt and regionalist rivalries were still simmering. In May 1827, the Acropolis, the last Greek bastion in Roumeli (Central Greece), fell to the Ottoman army. Nevertheless, Kapodistrias’s diplomacy and, above all, the three Great Powers‘ pursuit of geostrategic interests played a more important part in the final outcome of the Greek Revolution. In view of the new Tsar’s expansionist ideas, the British and French decided to enter into an agreement with Russia, and call upon the Ottoman Empire to grant Greece its autonomy. The Treaty of London was signed in July 1827 but the High Porte did not comply with the terms.

The three Great Powers thus triggered a clause in the agreement authorising them to intervene in order to enforce the Allied demands. Their forces would decisively defeat the Ottoman and Egyptian fleet at the naval Battle of Navarino in October 1827. In August of 1828, a French expeditionary corps led was dispatched in the Peloponnese, while the Greek cause was also aided by the outbreak of the Russo-Turkish War of 1828–1829. In February 1830, the Great Powers signed the third London Protocol, recognising Greece as an independent, sovereign state.

Establishment of the Greek State

In Greece’s first years as an independent country, Kolokotronis showed his unequivocal support for Governor Kapodistrias, although many of his own previous allies expressed dissent. Kapodistrias’s rivalry with the kodjabashis and former military leaders culminated in his assassination on 27 September 1831 (O.S.), which was followed by a period of widespread unrest.

Following the assassination, an Administrative Committee was established to temporarily assume the executive powers that had been left vacant. It was presided by Kapodistrias’ brother Augustinos, and its other two members were Kolokotronis and politician Ioannis Kolettis. However, negotiations with the Fifth National Assembly were fruitless, and soon Avgoustinos dismissed the other two members of the Committee. A deep rift had broken out between the supporters of Kapodistrias and those pushing for the introduction of a constitution. In March 1832, Avgoustinos Kapodistrias resigned and left the state of Greece.

Kolokotronis refused to be part of the Administrative Committee that was formed in April 1832. In 1832, Greece was established as a kingdom, and throne was offered to the young Prince Otto of Wittelsbach, son of King Ludwig I of Bavaria. The Fifth National Assembly confirmed the selection of Otto in July 1832. Otto arrived in February 1833 but was still considered a minor, so a regency council ruled in his place. Its authoritarianism and distrust of the Greek political parties led to a quick eroding of its popularity.

Theodoros Kolokotronis on the catafalque, Johann Jacob Weber (MDZ München via Wikimedia Commons)

Trial, rehabilitation and final years

The regency council was particularly hostile to the supporters of the Russian Party who, in turn, appealed to the Tsar asking for the dismissal of the regency and the immediate assumption of power by Otto. A political crisis soon broke out, and two members of the council denounced a supposed conspiracy. Kolokotronis, who had been kept out of military command due to his pro-Russian sympathies, found his name linked to these alleged machinations; in April 1834 he was put to trial together with his son Gennaios and the generals Plapoutas and Kitsos Tzavellas and imprisoned in the Acronauplia citadel.

In March, Kolokotronis and Plapoutas were formally charged with high treason and in May they were sentenced to death, although King Otto soon intervened to commute the sentences to imprisonment. Two dissenting judges, Anastasios Polyzoidis and Georgios Tertsetis, refused to sign the decision resulting in their dismissal from office and prosecution. This led to further alienation with the majority of the Greek people, while a vicious uprising broke out in Theodoros’s homeland of Mani.

In June 1835 Otto reached the age of majority, ending the regency; one of his first acts was to grant pardon to Kolokotronis and the other imprisoned fighters. Kolokotronis was in fact reinstated as a General of the Greek army and appointed member of the newly founded Council of State, created as an advisory body to the king. He would retain friendly relations with Otto for the remainder of his life, eventually becoming his aide-de-camp. During his final years, he dictated his memoirs to Georgios Tertsetis –one of his trial’s dissenting judges– who would publish them as a narrative biography in 1851.

Theodoros Kolokotronis died of a stroke on 4 February (O.S.) 1843, having returned from a reception at the royal palace. He was given a grand funeral in Athens, attended by vast crowds along with every surviving hero of the Greek Revolution. His son Gennaios would go on to become Prime Minister (the last one appointed by King Otto) in 1862.

Legacy

Several biographies of Kolokotronis have been published in Greece, his name has been given to squares and streets, while his portrait has been used on banknotes. He has been immortalised in statues and busts in several public sites across Greece, especially in Athens and the Peloponnese, the most famous of which are the bronze equestrian statues in Athens and Nafplion, created by Lazaros Sochos. Most important of all, his name has been inextricably linked with the Greek War of Independence and the phrase “hero of 1821” in the collective subconscious of the Greek public.

Source: greeknewsagenda.gr