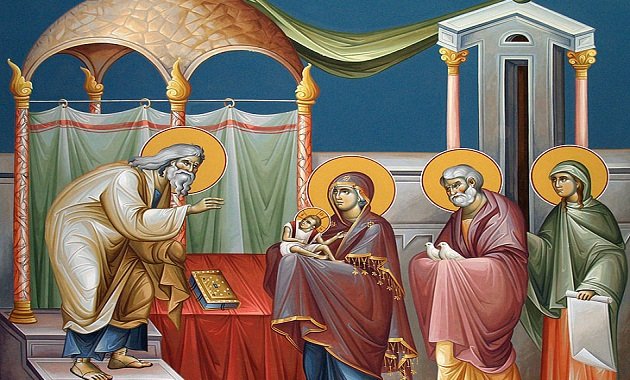

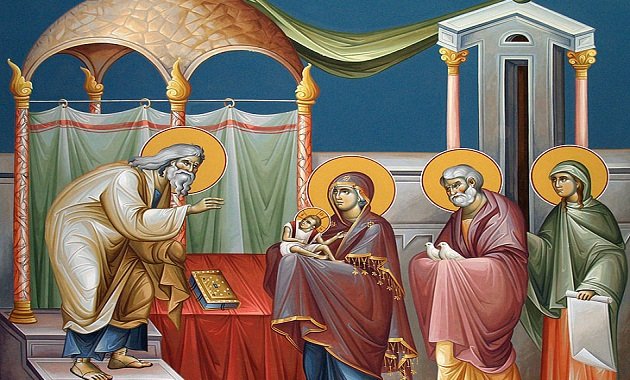

The Feast of Christ’s Reception as Fulfillment of the Ritual of Mosaic Law

The recent feast, the Reception of the Lord, is the feast which is celebrated exactly forty days after that of His Nativity. The name of the feast in Greek comes from a verb meaning ‘to go out and meet or welcome someone’ [Hence the depiction of Symeon in icons as being at or outside a door. WJL]. As regards the determination of the celebration of the feast on 2 February, this was decided in the 6th century, at the time of Emperor Justinian. It was fixed on this day because it is the fortieth after Christ’s birth, which, it had been decided in the 4th century, was to be celebrated on December 25.

We draw our information regarding the event of the Lord’s Reception from the Gospel according to Saint Luke. In the narrative in chapter 2 of this Gospel, the Evangelist mentions two fundamental details: a) the circumcision of Jesus Christ exactly eight days after His birth (Luke 2, 21); and b) the entry of the divine infant into the temple in Jerusalem 40 days after His birth, as required by the ritual contained in the Mosaic Law (Luke 2, 22-39).

What Saint Luke relates in his Gospel are not random events, nor do they take place at the personal behest of some individual, but rather they occur in accordance with a certain ritual, which is described mainly in the book of Leviticus, the third in the series of the historical books of the Old Testament.

According to Leviticus, a woman who became pregnant and gave birth to a male child would be unclean until the eighth day after the birth, the day on which the circumcision would take place. She would then remain unclean until the fortieth day after giving birth, when she would be cleansed of her blood. Until then, she was forbidden to touch anything sacred or to enter the temple before the time of her cleansing had passed. If a woman gave birth to a daughter, however, the number of days for her purification numbered 80 (Lev. 12, 1-5). On the one hand, this excerpt from Leviticus ordains what the woman is to observe during the period of her lying-in and, on the other, makes clear that, however harsh the Law was towards her, it also protected her from sickness and made her rest, in order to recover from the pains of birth.

Thereafter Leviticus mentions the ceremonies which take place during the purification. It provided that, as soon as the proper number of days had been completed, the requisite animals without blemish should be brought to be sacrificed to the Lord and to purify the woman (Lev. 12, 6-8). Despite what many and varied people thought, these sacrifices had absolutely no magical meaning. Their aim was the restoration of relations between the woman and God, as regards [her ability to enter] the sacred place.

Naturally, this ceremony could hardly be divorced from the whole of the rest of the Law of the Old Testament. On the contrary, it is indissolubly linked to the Lord’s command regarding the offering of the first-born in the narrative of the book of Exodus. This book presents God as giving the commandment to Moses that every Israelite should dedicate to God every male first-born, man or beast (Ex. 13, 1-2).

This dedication demanded by God was required as an indication of gratitude and recognition on the part of the Israelite people towards God, Who redeemed His people from slavery in Egypt. It was also a reminder of the time when the angel of death passed over the first-born children of the Israelites but destroyed those of the Egyptians. Regarding the offering of the first-born animals, the Law of Moses is clear and makes a distinction between clean and unclean species. The first-born of donkeys are not suitable for sacrifice, so they were replaced with an agreed sum of money. The same monetary exchange was also true for people, since God did not accept human sacrifice. Cyril of Alexandria notes that ‘He Who created all things in incorruption, had no desire for human sacrifice’. This is why, in the thirteenth chapter of the book of Exodus, where the sacrifice of the first-born is discussed, the following is mentioned: ‘You shall set apart every [offspring] opening the womb, the males, to the Lord. Every one that opens the womb out of the herds or among your cattle, as many as shall be born to you, you shall sanctify the males to the Lord. Every [offspring] opening the womb of the ass you shall change for a sheep; and if you will not change it, you shall redeem it. You shall redeem every first-born of one of your sons’. (Ex.13, 12-13).

So the divine infant was also offered to God, as the first-born son of the Virgin, as had others in the past of the Israelite people. The judge and prophet, Samuel, Jacob and other personalities in the Old Testament had opened the sterile and barren wombs of holy women and the fruits thereof were offered to the Lord and were also declared to be ‘holy because of the Lord’.

Source: pemptousia.com