Greece buoyed by Turkish official’s comments on Parthenon Sculptures taken by Britain

One of the world’s most intractable cultural disputes is back in the spotlight after a Turkish official cast doubt on the existence of proof long cited by Britain that it had legally acquired the Parthenon Marbles , 2,500-year-old sculptures taken from the Acropolis in Athens.

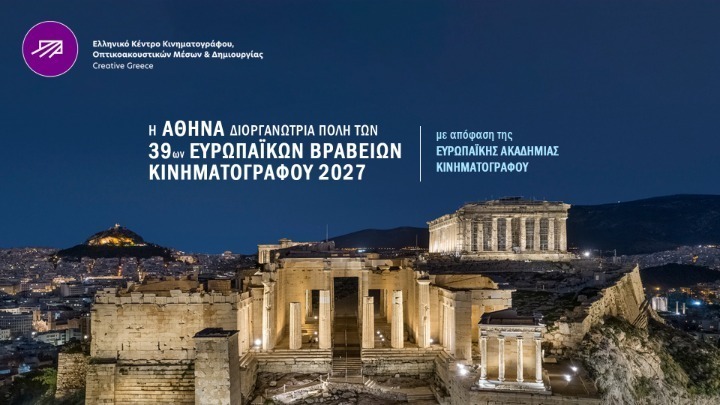

Greece’s culture minister said the comments made at a UNESCO meeting in Paris last week on the return of cultural property bolster Greece’s argument that the sculptures were illegally removed from the Parthenon temple on the Acropolis and should be returned.

The antiquities, also known as the Elgin Marbles, were removed in the early 19th century by Lord Elgin, Britain’s ambassador to the Ottoman Empire which ruled Greece at the time, and are housed in the British Museum in London. Greece has long campaigned for their return.

The museum maintains Elgin removed the sculptures legally after Ottoman authorities granted him an imperial edict, or “firman,” allowing him do so.

But Zeynep Boz, the head of the Turkish Culture Ministry’s anti-smuggling committee, said at a meeting of UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property in Paris that no such document has been found.

As the successor to the Ottoman Empire, “Turkey is the country that would have the archived document pertaining to things that were sold legally at that time,” Boz told The Associated Press Wednesday. “Historians have for years searched the Ottoman archives and have not been able to find a ‘firman’ proving that the sale was legal, as it is being claimed.”

Boz added she felt obliged to intervene during the UNESCO meeting after a British participant said in his speech that the Elgin Marbles were bought legally during the Ottoman era.

“To have remained silent would have amounted to acknowledging the British claim,” she said. “I had to say: ‘We are not aware of such a document’.”

The only known existing document referring to the imperial edict is an Italian translation.

However, Boz said it has “no signature, no stamp, no tughra (official seal of the sultan). Nothing to make it official. The document it allegedly refers to is nowhere to be found.”

While ties between Greece and Turkey are often strained and the two countries are at odds over a wide series of issues, including territorial claims, both seek the return of cultural artifacts removed from their territories and currently housed in museums around the world.

Greek Culture Minister Lina Mendoni said the comments bolstered Greece’s argument that Elgin illegally removed the sculptures.

“There never was an Ottoman ‘firman’ granting Elgin the permission to treat the Parthenon Sculptures with the brutality with which he did,” Mendoni said Tuesday. “Turkey’s representative (at the UNESCO meeting) confirmed what the Greek side has been arguing for years. That there was no ‘firman’.”

Mendoni said Greece remained “open to dialogue” and would continue its efforts for the return of the sculptures, which have a place set aside for them in the Acropolis Museum in Athens.

While the British Museum is banned by law from permanently returning the sculptures, its leaders have held talks in the recent past with Greek officials about a possible compromise that could see the sculptures displayed in both Athens and London.

Those efforts suffered a setback last November, when a diplomatic spat erupted over the marbles and British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak abruptly canceled a planned meeting with his Greek counterpart, Kyriakos Mitsotakis.

Asked about Boz’s comments, the British Museum referred to a statement it gave to the UNESCO meeting reiterating its desire for a “Parthenon partnership” to resolve the dispute, and said it had nothing more to add.

“The British Museum recognizes the strong desire of Greece for the Parthenon Sculptures in London to be returned to Athens,” the statement said. “This is a question with a very long history, and we understand and respect the strong feelings that this debate commands.”

It said it was “keen to develop a new relationship with Greece – a ‘Parthenon partnership’ – and to explore the possibility of innovative ways of working (with our Greek friends) in the hope that understanding of the Parthenon Sculptures deepens and continues to inspire people across the world.”

Source: AP