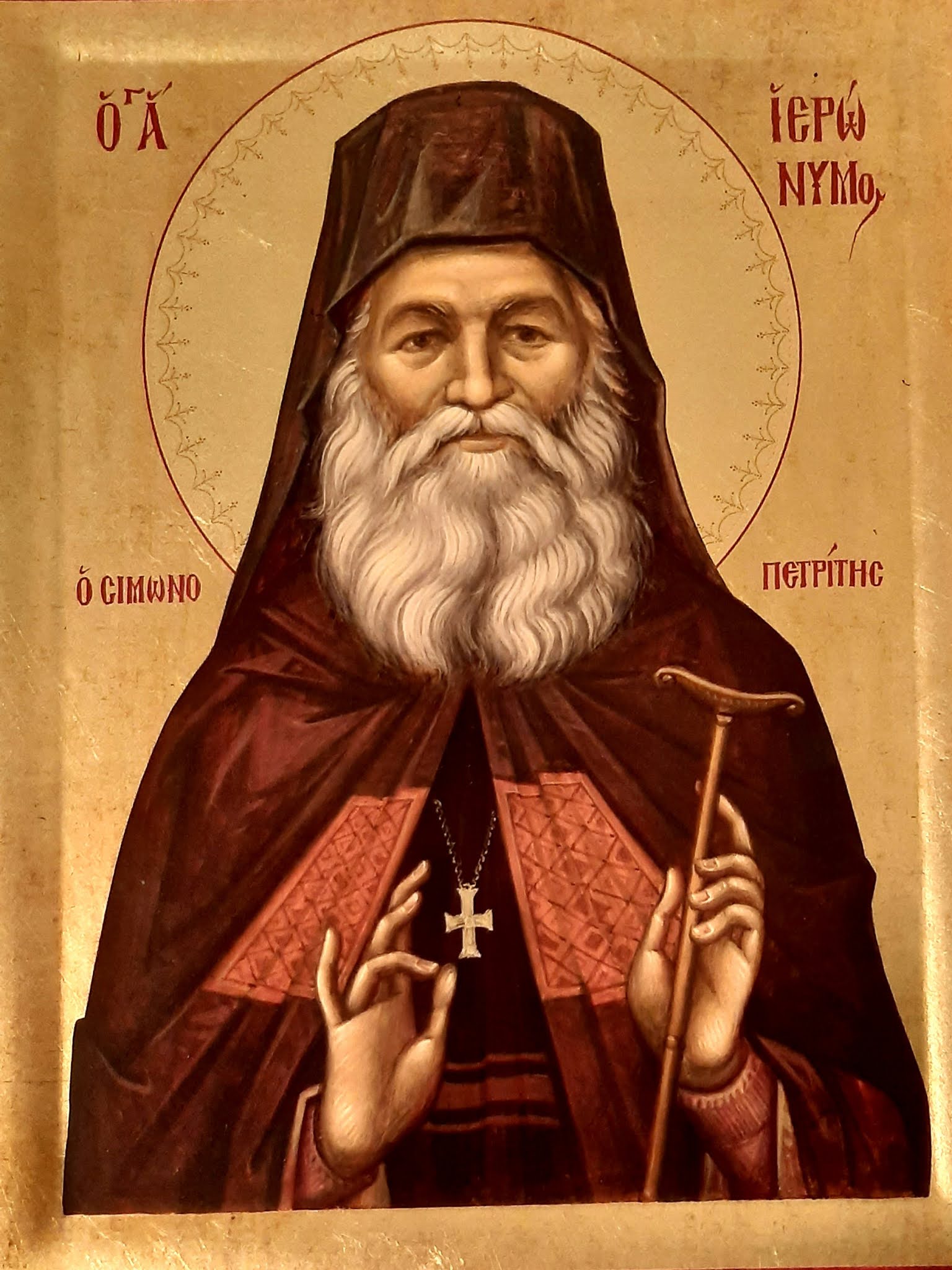

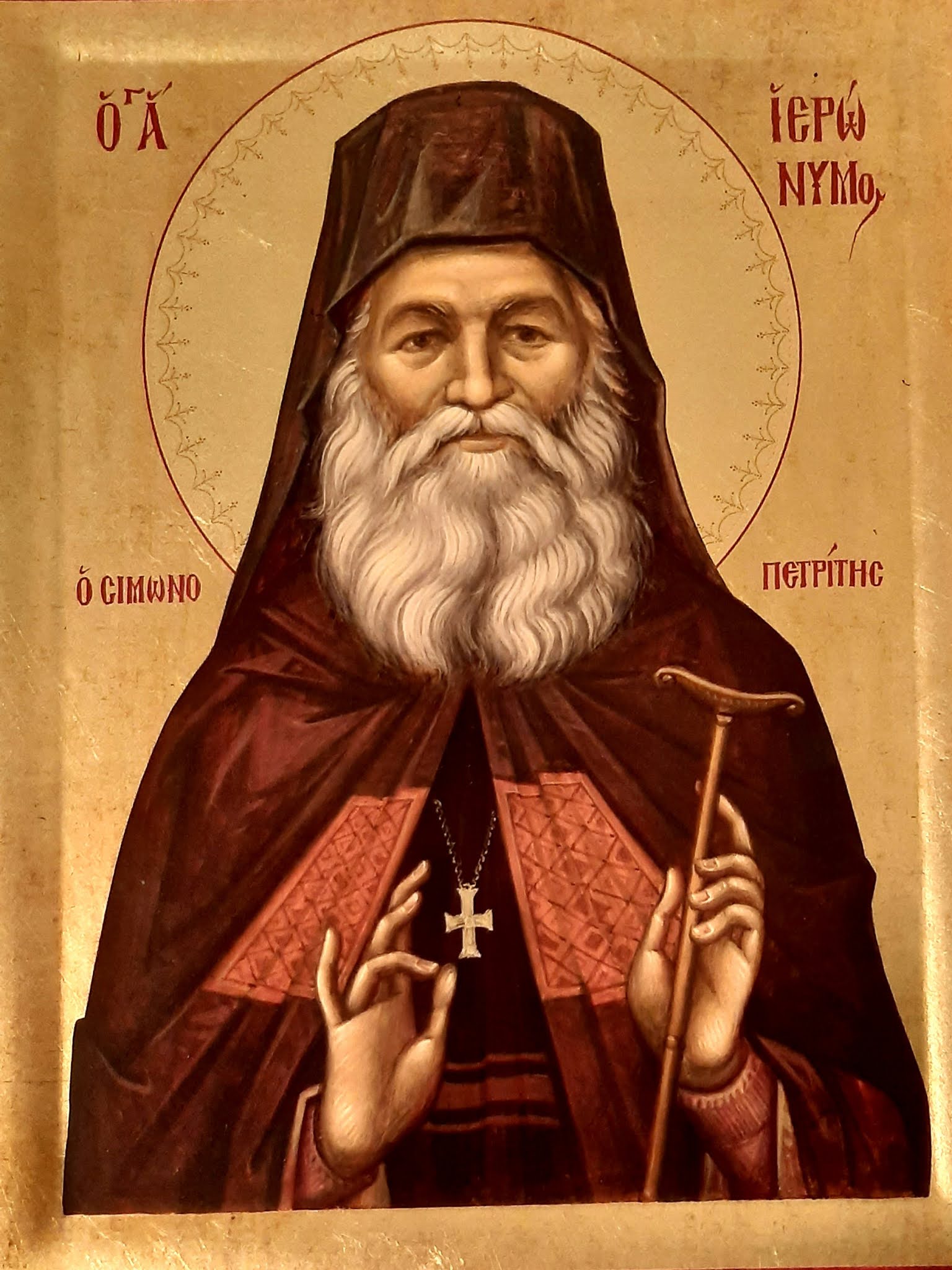

Elder Ieronymos of Simonopetra (1871-1957)

Childhood Years (1871-1888)

Elder Hieronymos was born in the village of Reïz-Dere in the Krini region of Asia Minor in 1871 to poor yet pious parents, Nicholas and Maria Diakogiorgis.

The village was entirely Christian and was five kilometers northeast of Alatsata [Alaçatı] and two and a half kilometers from the sea. Most of the inhabitants were farmers or vine-growers and had come originally from Crete or the Peloponnese.

At his baptism, he was given the name John. When he went to school he was a good student, surpassing the others in intelligence and maturity. As soon as he completed Primary School, the teacher sent him to the neighboring little town for a short time to work as a teacher.

he village church became the center of his life. It was here that he found what his soul was looking for: joy and God’s blessing, which were poured out upon him through the sacraments, prayers and services. He loved the services, the priests, the singers, the vigils and the chapels. He assisted the singers in the choir and the priests in the altar. He seemed to be older than he actually was because of his silence, seriousness and piety.

As a child of poor parents, he knew hardships from an early age, and later, as a monk, he would undertake these voluntarily and faithfully. We know very little about his childhood, but his mother clearly left the imprint of her love on him. It was from her that he first heard the lives of the saints, that he learned to fast, to pray and to love God. The saints were among his first friends. His family often discovered that he would go missing, but they knew they would find him in the chapels. He was cured by Saint Demetrios on two occasions: once when he had terrible pains in his legs and again when he had chicken-pox. Both times he stayed in the church of the Saint for forty days and fasted.

One evening, he heard his sister saying the Salutations to the Panagia. In the morning, she asked him if he knew the Salutations. When he said that he didn’t she told him: “Now is your chance to learn.” “From the age of seven I knew the Salutations by heart,” the Elder would later say.

His mother’s great faith became apparent before her death when she donned the monastic schema, which she loved since her childhood. She was renamed Melania. His brother became a monk with the name of Maximos and there were three nuns in the family, Magdalene, Melania and Kassiani, two of whom had previously been married. He also had more distant relatives who entered monasteries on the Holy Mountain or other parts of Greece.

At the age of twelve, he went to Chios with three other young boys to see the famous, discerning Elder, Saint Parthenios. The Elder was bent double and completely covered, so that the flesh on his face and hands wasn’t visible. He lived in great asceticism in a cave next to the monastery of which he was the founder. He welcomed them by name, even though it was the first time he had seen them. He told each of them the path they would follow in life, and was happy to tell John that he would become a monk.

Fr. Hieronymos later wrote: “During my teenage years, I would think about how I could please the Lord. I chose the good and God-pleasing life of the monks because it’s best suited to anyone wanting to follow the Lord with patience and devotion. He Himself says ‘Come to me all of you who are weary and heavy-laden and I will give you rest.’ After receiving my father’s blessing and the best wishes of my parents, as well, of course, as the Cross of the Lord as an invincible weapon, I went to the Holy Mountain of Athos, since this this was the most suitable place and in accordance with my God-pleasing aim and decision.”

His father told him: “Go and don’t come back.” He said this because some would go but would then return home. He wanted his son to be serious.

Elder Hieronymos as a Monk on the Holy Mountain (1888-1920)

Young John arrived on the Holy Mountain, made the sign of the cross and thanked the Panagia. Here his love for the Mother of God grew, to such an extent that, to his dying day, he would weep at saying or hearing her name. At the time when he arrived, there were more than 10,000 monks on Athos. Praising God, the seventeen-year-old John entered that holy location and passed through the gates of the Monastery of Simonopetra, in order to imitate the achievements of the saints of God. This was on 3 October 1888 and, on the 28th of the same month, his name was entered in the book of novices.

As he later wrote: “I was received by the Abbot, the venerable Elder, the late Archimandrite Neophytos, who was from Alatsata [close to John’s home village], and I was received as a novice, performing regularly any task to which I was assigned.”

The life he began there was one which thousands of monks had led before him: a life steeped in the remembrance of God, a mystical life with long daily services, frequent vigils and regular fasts. It consisted of the rule, duties, confession and holy communion. And in the midst of these everyday tasks, he continued where he had left off back home, rejecting anything that was superfluous. He began to study the Scriptures, the ascetic fathers and the lives of the saints, drenching the pages of the books with his tears.

One of his first duties was that of ‘konaktzis’, looking after the ‘konaki’, the house where the monastery’s representative in Karyes [the capital of the Holy Mountain] lived. He returned to the monastery after two and a half years, because of illness. For a short time he was sent to Dafni [the port of the Holy Mountain] and, for a few months to the dependencies on Lemnos as cellarer [These dependencies were vital to the monastery which sent logs from its forests and brought back wine, for which the island was famous]. His obedience to the monastery’s authorities is an indication of his humility.

After four and a half years of testing, on Palm Sunday 1893, he became a Great Schema monk, taking the name Hieronymos [Jerome] and he kept the date of June 15 in high regard, as being date of the commemoration of his patron saint. Once he was tonsured, new and greater struggles awaited him. One of the elders wrote about him: “He burnt more petrol on reading than he drank water” [petrol was used for the lamps]. He was always quiet, because he was internally vigilant. Often, when he was alone, he would shed rivers of tears. He would never go near a fire, even though it was sometimes very cold. He never gave rest to his body, but would only snatch a little sleep sitting in a chair. And no human tongue can describe his abandonment of any personal property. This monk was the support of the monastery. He would be ready with advice on the most insignificant of issues. He was entirely humble and was the pride and joy of the monastery.

Out of respect for his monastic strivings, the brotherhood increasingly turned to him. They sent him the novices to be introduced into the monastic spirit. He spoke to them with great discretion. One late elder, who was then a novice, wrote about what Elder Hieronymos told him: “Have you come here to become a monk? Have you thought about it properly? The monastic life is a little rose for those who are pure. When you finish the duties that have been assigned to you, you go to your room and sit on the stool. There you will voluntarily acquire self-reproach and you will think about the fact that there is no other person for you, only our Lord Jesus Christ, who took away the sins of the whole human race. Then you will begin the invisible warfare. When you say the sweet name of the Lord Christ, protect all the parts of your senses, which are glorifying God, lest a devil from the right should enter and separate you from the Lord’s love through familiarity or pride.”

The young monk Hieronymos became the monastery’s secretary, a duty he retained as Abbot. They then appointed him to the difficult task of overseeing all the external affairs of the monastery. He was obliged to leave the Holy Mountain regularly, meet with a variety of people and bring his affairs to a satisfactory conclusion. Early on he was appointed to responsible and difficult tasks involving visits to the monastery’s dependencies. Without reservation, with exemplary obedience, he rose to the challenge of the demands of the monastery’s overseers and spent long periods outside the monastery. He was involved in financial and administrative matters, but never for a moment lost the sense of his monastic calling or the need for inner communication with God.

His courtesy, perfect obedience and respect for the monastery and its overseers continued throughout his long life. His great progress in the monastery, the felicitous conclusion of all the tasks assigned to him and, particularly, his modesty, gentleness and virtue in general made him, on the one hand, well-liked and respected, but on the other, as is often the case, also made him the object of jealousy, envy and pettiness. His answer was always silence and forbearance.

At the monastery they would see his lamp burning all evening long. The older monks used to say they never saw him lying down. Whatever time you went to see him, you would find him on his feet or sitting. He slept in his chair. Too much sleep reduces our love for God. In the morning you would see him at the service, in his prayer-stall, or singing, reading and directing the service. One elder recalls: “He would check up on us. I would go to the stalls at the back, so that he wouldn’t see me, because I was ashamed of myself.” And he was very strict with his fasting. He never ate anything except at the appointed meal-times. Whenever he was at the monastery, he never missed a service. Nor did he eat all his ration in the refectory. Usually he would do the reading during the meal and then eat afterwards, so as to hide what he was doing. According to Papa-Euthymios, whenever he returned from outside the Mountain, he would go for days without oil, in order to make up for any infringement of the fasting rules. His spiritual struggles were many and varied, but he kept them to himself.

On his return from his travels, he didn’t stop working. He would write in the secretary’s office and in his cell, organize the library and archives, and study. He served in church and took part in common tasks. No duty was beneath him, which is why God elevated him.

In 1910, he was in Athens for about six months, as steward at the Dependency of the Ascension (Analipsis). In his correspondence with the monastery, he tried to persuade the brotherhood not to sell the dependency. His forecast of a future recovery for the monastery was soon borne out. It was here that he first became acquainted with the congregation at the church and this relationship would later blossom and bear fruit.

In 1911, on his return to the Holy Mountain, he survived a shipwreck, attributing his escape to divine providence.

He found great support in the relationship he developed with the saints of the Church. We’ve already seen his relationship with Saint Demetrios and the cure effected by the latter for him. But he also had special affection for Saint John the Theologian. He had a hernia from an early age, which he took care of himself, though it wasn’t at all easy for him. He later wrote: “I was cured quite painlessly, without medication or an operation.” His cure came at the vigil for the feast of Saint John on the 26th of September. “I had made the sign of the Cross and called upon the Saint, then went to the choir stall to start singing ‘Lord, I have cried.’ Just then I felt the hernia disappear, and it hasn’t bothered me since. I was cured miraculously, by the invocation of the Theologian, whose wonderworking grace and help I gladly confess, praising God who is wondrous in His saints. My cure was effected in 1897.” The Saint also visited him at another vigil and freed him of intense impure thoughts. Thereafter he was never again afflicted by this passion and such thoughts.

His love for the saints was so great that it pleased God that he should meet the most ascetic Saint Parthenios of Chios shortly before the latter’s demise. He was connected, in personal friendship, with Saint Nektarios, Saint Savvas the New of Kalymnos, and Saint Nicholas Planas.

This intense love of his for the saints found poetic expression through the gift he had from God of singing and writing hymns. So it was that, immediately after his tonsure, in 1893, at the age of 22, he wrote eight canons, one in each tone, to ‘Our Holy and God-bearing Father Simon, from whose relics myrrh flows,’ as substitutes for those lost in the fire of 1891. In 1896, he composed a supplicatory canon to the monastery’s saints, Simon of the Rock [from whom the monastery takes its name] and Mary Magdalene [her left arm is kept at the monastery]. These he published in 1924, together with musical settings for their services and the eight canons he had composed to Saint Simon.

In 1902, he wrote and set to music a service for Saint Ephraim the Syrian and supplied other missing material, such as services for Saints Neophytos and Ioannikios, after whom his own elders were named, Saint Sophronios, the 99 Saints in Crete, Saint Jerome, and Saint Mary Magdalene. His hymn-writing activities continued with a supplicatory canon to Saint Anthony the Great, Salutations to Saints Menas, Victor and Vikentios, Paul the Patriarch of Constantinople, and Sergius and Bacchus. He made additions to the services of other saints whose holy relics are kept at Simonopetra, and wrote verses of prayer and entreaty to the Lord, the Panagia and various saints. Many of these works remain unknown or are inaccessible. His main contribution, however, was his constant, heart-felt participation in the daily services and his unceasing prayer.

In February 1914, despite his objections, he was honored by being voted Overseer and a member of the Committee of Elders. In all his labours and travels, he never forgot his monastic duties. On the road, on a ship, on a train, he had his prayer rope.

He was the attendant of Abbot Ioannikios during the latter’s serious illness. On 7 December 1919, he closed the eyes of his second Elder, whose last wish was that his beloved and worthy spiritual child, Fr. Hieronymos, should take over the position of Abbot. It’s worth pointing out that never in his life did he seek, much less strive for, anything. He was always patient and refused every honor and distinction. For years he was asked to agree to ordination, but wouldn’t consent.

Elder Hieronymos as Abbot of the Monastery (1920-1931)

In the proceedings for 2 January 1920, he was proposed as a candidate for the office of Abbot. In the same year, Metropolitan Irinaios of Kassandreia ordained him deacon on April 11 and priest on April 12, also raising him to the rank of archimandrite and spiritual father, by the laying on of hands. On 18 April, the Sunday of the Myrrhbearing Women, he was given the Abbot’s staff, by a unanimous decision of the brotherhood.

In the first months of his tenure as Abbot, he again had to leave the monastery to look after its affairs. Arriving by ship in Piraeus, instead of going to the Dependency of the Ascension as arranged, he took another ship, to Aegina. There he visited Saint Nektarios, who was ill by this time. They had known each other since the Saint’s first visit to the monastery in 1898. Thereafter they developed a spiritual bond, which was maintained through Elder Hieronymos’ visits to Athens.

It was the eve of the feast of the Holy Trinity, which the monastery in Aegina celebrated. The Saint lay ill in bed and was unable to preside at the vigil. The nuns asked him if they should ring the bells. He replied: “Ring the bells. The priest is coming.” As they rang the bells, Elder Hieronymos entered the monastery. “Didn’t I tell you the priest was coming? And he’s the abbot of a monastery on Athos,” the Saint said to them. After the vigil was over, the Saint asked Elder Hieronymos to visit all the cells of the nuns, in order to bless them. But he didn’t want to obey God’s bishop and slipped quietly away. When he told the story later, he wept, saying: “Who was I compared to a saint?” He always remembered the Saint’s request, however, and, three days before he departed this life, in 1957, he went and blessed the nuns’ cells.

A month before the repose of Saint Nektarios, Elder Hieronymos managed to get to see him in the hospital where he was. It was his nameday, 11 October, 1920.

In August, 1921, he was appointed by the Holy Community to the five-man committee tasked with drawing up a draft constitution for the Holy Mountain.

His administrative duties and his many other responsibilities didn’t prevent him from devoting many hours to the service of the brotherhood. He worked alongside them at their tasks. Morning would find him kneading bread in the bakery, in winter he would help with clearing the snow from the courtyards, in the afternoons he would be in the gardens and at night he would wash his clothes. In this way he provided an example of humility and hard work. His own Elder had taught him long before to be the first among servants.

But his great and secret struggles continued. He did not cease sleeping little, either on the chair or on the couch, with a pillow on his back. Simonopetrites of old narrate how the door of his abbacy was never found to be shut, he waited for you no matter what time you would visit, while he was studying or writing. He continued to be the same in simplicity, humility, receptiveness, nobility, asceticism, discernment, inconspicuous, and submissive as he was before. His abbacy was distinguished by spiritual fruitfulness, austerity, hospitality and charity, hard work, diligence and confidence in the providence of God.

In 1924 the calendar reform took place and at the feast of the Annunciation he liturgized for the first time with the New Calendar at the Dependency of the Ascension. This provoked a strong reaction in the monastery, to the point where when he returned, he was banned from entering the church by a group of monks for six months. He calmly endured this without retreating from his post.

His whole life was a constant martyric struggle. But at the same time his whole life, his genuine stance, his few responses, his dignified attitude towards his accusers, his silence and his devotion to the will of God after a time proved true the testimony that he walked along the path of the crucified Lord and stood in the footsteps of so many misunderstood and slandered saints.

The calendar issue on the one hand, which was due to the indiscriminate zeal of some, and the intense localism on the other hand, of those who in no way wanted monks from other places except their own region of Asia Minor, as well as the Elder’s non-love of money and charity, together with the fathers being unable to comprehend his spiritual life, made him “grievous to behold” (Wis. of Sol. 2:14). This resulted, after an eleven year abbacy adventure, in him being slandered within the monastery for financial mismanagement, and by a decision of the Holy Community, at the end of June in 1931, he was exiled for six months to the Monastery of Koutloumousiou. The fathers of the monastery treated him with unlimited love and they considered him a saint. He confessed that he was suffering for his sins. His exile and then his mission to Athens became the cause of the salvation of many souls.

The Holy Community indirectly recognized his innocence and interrupted his exile after four months to send him to the Dependency of the Ascension in Athens. His unjust punishment led him to glorify God, to manifest and utilize his talents, and to unfold his virtues and his gifts. There he made his second great renunciation. For 26 whole years he lived there, from the age of 60 to 86, as an Hagiorite outside of the Holy Mountain, without ever returning there again. He made the place of his exile the place of his service and he carried with him the genuineness of the Holy Mountain to the hill of the Ascension, thus making this mountain holy to which others would come.

In 1937, after the resignation of the abbot Kaisarios, the managers of the monastery proposed for him to become the abbot. With respect, love, humility and dignity he refused to accept it considering his powers to be inadequate. In a letter he wrote: “And with my Sacred Repentance I shall in no way profit, for I shall cause harm in the utmost, not being able to cope with my duties and what my position and great ministry requires.”

Elder Hieronymos at the Dependency of the Ascension (1931-1957)

Athens in 1931 was a city with a low level spiritual life. The Fathers of the Church were virtually unknown. Monasticism was regarded as an old glory of the Church that was not needed today. The city was full of poor people. It was a poverty that was inherited – by orphans, through wars, and by refugees. At the settlement of Byron, where the Dependency of the Ascension was located, refugees from Asia Minor lived there, who continued to maintain their pure lay piety and who gladly accepted him as God’s messenger.

Until the end of his life illnesses would not leave him – continuous fevers, headaches, weakness, fatigue, bronchitis and blood illnesses. When he reposed his entire body was full of cancer. He never said how much pain he was in. In his perseverance and by the love of doctors he took medicine. One day he refused to take his medicine, saying: “Not today, it is the feast of the Holy Unmercenaries and they are physicians.” After his repose they found a lot of unused medicine in his cupboard. The pressure of the doctors did not allow him to admit the need for them and give the flesh what it needed. Voluntary and involuntary pain is an ascetic exercise, which is a means towards sanctification, a proof of submission to God.

Moreover, the various temptations never left him. He would say: “They are as necessary as breathing. Temptations are like the waves of the sea; without waves one cannot travel and without temptations one cannot be saved.” His experience gave him the comfort to talk to his children about the great benefits of temptations, which only tire carnal people.

He patiently loved everyone. Instead of the Elder being annoyed when someone was bothering him, his spiritual children were greatly saddened, to whom he said: “Keep calm, despite all this he still loves me.”

In 1949 his monastery, after slanderous complaints, considered recalling him. They mainly accused him of “wasting large amounts of money.” The love of his children did not allow the recall to take place. In the many warm letters to his monastery, respect and love towards him is revealed.

The recall did not take place, but decisions were made binding for him a comfortable course for his spiritual work. He endured it all, with the humility that distinguished him, without discussion and objection, but not without pain. He had surrendered all to God, and he only looked towards Him. Neither did praises give him joy, nor did accusations give him sorrow.

His first visitors were mainly ordinary people in the surrounding area. His love made him famous, so that the bench outside his confessional was never empty of people, who had been waiting patiently for their turn for hours. Many people came to entrust to him their pain. As austere as he was towards himself, the more lenient he was towards others. Fr. Hieronymos was primarily the spiritual father of a large crowd wounded by sin. He stood as a tender physician, an excellent curator of souls, a friend who sympathized with the defeats and rejoiced with the victories, a discreet guide, a careful counselor, tireless, calm and sweet.

In the early years he would confess standing up. He would begin after liturgy and would end many times after midnight. Often, in order to gain time, he would eat or read letters and confess. Every time his answers showed how much he carefully listened. Even though many waited for him, he was never in a hurry. This was true even when he was sick. He would say: “Go on, let the others wait. I want to listen to you.”

He saw souls as an open book. His knowledge of the human soul was amazing. Rarely did he ask questions from those who confessed. When he would be asked why he doesn’t help with questions, he responded: “I don’t want to put sins on you that you didn’t think of yourself. Everyone knows well what they have and what burdens them.” Before the confession he would always offer something, he would smile, he asked about your work, and then he would put on his priestly stole.

He would listen carefully to confessions then he gave a response. Sometimes he looked like he was sleeping or he would close his eyes either due to fatigue or to concentrate, to increase his attention and give comfort to the one confessing, so as not to look them in the eyes.

He utilized everything to help those who were hurting, not counting the time or effort. His greatest joy and reward was when he saw people who were truly repentant. Sometimes, if you did something wrong, he tried in various ways to bring you into such a state of repentance in order to manifest it, without offending you or hurting you in the slightest. He had an ancient nobility, one that all spiritual people are adorned with. His greatest sadness was seeing souls come out of the confession with yet another sin. A willful confession that wasn’t pure.

In the end he warmly thanked you, because you trusted in him. If you went for the first time, he would keep your name, and pray for you daily. He did not allow you to feel hopeless. He knew how to comfort souls. “This is why I’m here, this is my job,” he would say. He would talk about the infinite mercy of the All-Good God, the intercessions of the Saints and of the Theotokos.

The Spiritual Gifts of Elder Hieronymos

His discernment and humility was covered also by the gift of foresight and clairvoyancy of souls and the future. This was the result of his great love for God and the illumination he received from Him. He knew the secret depths of the human soul. He saw the entire human being. What he asked for most of those who went to confession to him was a sense of their sinfulness and humility. Full of love for suffering human nature he truly saved the souls he received, those who showed him their sores and pain. His wondrous stole, repentance, the fiery prayer of the God-bearing father for divine mercy and forgiveness, gave meaning to people’s lives and opened paradisaical paths. He expressed himself not so much with terminology but with simple words. His illumined pure thoughts knew how to strengthen, bring joy and save. To all those who approached him he was a symbol of a wise spiritual father.

Services at the Ascension were daily, according to the Athonite typikon. At around two after midnight, which was the time the brothers at the monastery also got up, he went to the church to be by himself until five, when the service began daily. During this time he would remember certain names of the living and the reposed, because he did not have enough time during the proskomide. He had more than two and a half thousand names in his dyptichs. The daily services were simple, quiet and devout. The chanters were unselfish and honorable people.

The ceremonies of the Elder stood out. He transmitted grace to souls, with his bright face, peace and simplicity. Never did he sit down during the liturgy. As a liturgist, he was completely dedicated to his work. He appeared disembodied. During the time of the liturgy many children saw him standing above the ground. “The Father is flying,” they yelled. They would see him a span above the ground.

After liturgy he would not see people right away. He wanted to sit a few minutes in his armchair to keep quiet and shut his eyes. As he said: “After the liturgy I am disturbed, how my sinful hands touched Christ, and I want to be still and calm down.”

The relationship of the Elder with children, with whom he resembled in his love towards them, is one of the most beautiful pages in his blessed life. The descriptions of children then of this loving relationship are endlessly graceful and show, once again, his greatness. He talked to young children with great ease and seriousness about big issues. He trusted them, spoke to them like the elders, saying they understand more than we think, often in the plural. With the instructions he gave them, he opened their hearts to receive Christ and to keep Him there forever. With great sympathy he occupied himself with their school lessons, their educational progress, their health, their nutrition, their future, which he often foresaw, and tried to orient them towards their calling. He himself had a lot to learn by bending over the unpretentious childhood upheaval.

The charity of the good father remained proverbial. It reminded you of the lives of the great merciful saints. Almost all of the settlement of Byron was charitable from his hands, especially during the difficult days of the German occupation. He did not pay attention who asked, if they had need or not, but he gave generously to everyone. He tried to not keep any money in his cell overnight, which the love and respect of children offered him richly. When his money ran out, he borrowed money to help. When he had nothing he would say: “This is how it is, sometimes it is winter and sometimes it is summer.” Often he would get on the bus and didn’t have money for the ticket. His cassocks, his vestments, his undershirts and his shoes he would distribute when he had no money to give, so that no one would be sad. Such was his compassion towards his brethren. He would give with such joy it was as if he was the one who received them. He himself had extremely little, was a strict faster, was an example of having few things and self-sufficient. “A poor man from poor parents,” he would like to say of himself. When he reposed, there were only seven drachmas in his drawer!

Pages upon pages would be needed in order for people who knew him to write stories that referred to his gift of foresight. Without knowing someone, he told them their history and their name. He saw their thoughts, their hearts, their past, their future, not delving deeply into their psychology, but in order for them to live a prosperous life of purity and truth. What was worthy of astonishment was how simply he spoke of these things. He didn’t talk about events in the history of the world, of wars and so on. He spoke about the problems of struggling souls before him, to give them courage and comfort and dispel despair. He spoke in a mystical and allegorical way, as if it was natural to know the unknown.

He never spoke of his gifts. For him they were as if he didn’t know he had them, if they were even his. Indeed it was in those moments that God spoke through his mouth. His submission to God made him a support for others. He looked beyond all possibilities. The first thoughts God gave him he would give to the one confessing to him, so that he never erred. His gift was an offering of help to the world.

The healings of physical pain and sicknesses by the Elder were not few. He never believed and did not allow others to understand that he did miracles. What he knew and what he tirelessly preached is that God is near to us and he hears the prayers of the faithful. The prayers of the Church, with the sacred services, the divine Mysteries, especially that of Confession, Holy Communion and Unction, the saints with their intercessions, their icons and their relics, especially the Theotokos and the honorable Cross, all have the power to heal. And first and foremost, the one who heals, redeems and saves is Christ when He sees fervent faith in people. “The Lord God is your healer.” His weapons during these times of battle was his stole, his cross and his euchologion. Thus his hands took on great power. The faithful and unfaithful approached him and exclaimed: “We saw clearly that the Lord was with you.” With all the fire of his faith the Elder prayed to the Lord, who told His Apostles and their successors: “Heal the sick,… expel demons.”

The All-Good God, seeing the soul of the humble hieromonk Hieronymos, who from childhood gave of himself entirely, without keeping anything for himself, with asceticism, obedience, service to the brethren, how would He not give him the Grace to work wonders?

The miracles mentioned by devout people, his faithful spiritual children, are that which they saw and experienced near him. Many are still unknown as many have now passed away. Remarkably, some of them refer to witnesses who do not live so close to the Church. Their expressions reveal a secret appreciation to the true servant of God. The Elder’s extraordinary help made everyone respect him.

Similar testimonies of miracles and interventions after his repose are not few. This is natural, since now he is closer to Him whom he loved so much and is now richer in grace. Now his elderly body does not tire to hasten to those who are sick. Now he blesses his children from heaven, in order to further glorify the name of God who gives the gift to of miracles and is greatly generous.

From his time here on earth, due to his great love, God covered him with His Grace and he could not hide, just like the sun in a clear sky. The fragrance of his virtue was sensed with the physical senses.

In 1938, the Elder was invited to the funeral of Archbishop Chrysostomos. Though he was put in the line with the order of married clergy, he didn’t say anything. Next to him was a revered cleric who told him: “What is it with you Athonites that you are fragrant?” The Elder told him: “Shush blessed one, what do we have.” But he insisted: “No, I sense it, the fragrance is coming from you, you have something on you.”

Another spiritual child of his would say: “The further I got away from him the less was the fragrance, it was something between a carnation and a rose. I sensed a similar fragrance with Saint Nektarios.”

In an age of pure anti-monasticism, the Elder succeeded in inspiring a love of monasticism, and he dressed over three hundred souls in the monastic schema, without distinction of age or social status. There are not a few families who entirely dedicated themselves to God, his being the first. He would send monks to Mount Athos and other places. Nuns he would send to various convents. Some, due to their very advanced age, he tonsured and left them at their homes. Others he would send as laymen to monasteries, while others he loved to dress in the schema, either at the Ascension or in chapels. He read the klisi, which was engraved in the hearts of his children and he prepared them their path. With his entreaties he helped increase the angelic order of monastics. Seeing this increase, he could only thank the Lord and the Theotokos.

His Blessed End on 6 January 1957

The blessed Elder foresaw and foretold his death in many and various ways. He had made preparations for the journey to heaven from his youth. His whole life was a preparation for the welcoming of death, which he was looking forward to.

He was 86 years old and the severity of his illness troubled him for several days, but he did not interrupt his prayer and often made the sign of the cross. With no complaints, with patience, with good reason and calmness the end came.

A few days before his death, he was transferred to a clinic in Piraeus. Four days prior, following a divine vision, he visited the Monastery of Saint Nektarios in Aegina, despite the bad weather, to venerate the sacred skull of the Saint. His beautified soul from the many years of struggle left his much-contested body at 11:40 in the morning, on a Sunday, after the Divine Liturgy, 6 January 1957. His soul went up into the open skies. On the eve, the sacred Unction had been performed, and he received the Immaculate Mysteries. He made it also to drink Holy Water from the Great Sanctification of Theophany.

Immediately after his death, the political and religious press wrote much about his blessed life. The warm obituaries of many were hymns and thanksgivings to God, who granted them such a father.

A few days after the Elder was buried, some were sitting near his tomb, which is behind the Church of the Ascension, and they sensed a beautiful afragrance coming from him.

On May 8, 1965, his relics were transferred. Elder Gelasios of Simonopetra, who was sent by the monastery to receive his bones, said: “If the steward had not hidden them in the bell-tower of the temple I would have returned with an empty box.” With sacred longing all the people fell upon his grave to receive as a blessing and amulet some soil and wood from his coffin. Many had the opportunity again to sense strongly the signs of God’s grace. With astonishment they refer to the fragrance at the time of his transfer.

What he left behind as a picture and a sense of his face is remarkably described by the scholarly biographer Monk Moses the Athonite:

“The Elder was very simple. Short in stature. Even though he was a little bit euphoric he seemed disembodied and your gaze pierced him. His face was usually bright and stern, serious and kind. He would never leave off his monastic cap. The facial wrinkles on his face had a naturalness. His eyes were drooping, usually looking low, and rarely bright. It was difficult to look him in the eyes. He often wore simple eyeglasses. His look was graceful, warm, and he looked at you with an exact love. His smile had a special beauty. His beard was white, and in the middle it parted a little. It was usually pale. He was a simple monk with clean clothes and shoes, with great paternal gifts, kindness, tranquility, discernment and sympathy. The appearance of his face in general, underlined by the whiteness of his wavy hair, the simplicity of his clothes and his words, the grace of his meanings in warm phrases became a book of help to the anxious. ‘Their character shows in the way they dress, the way they laugh, and the way they walk.’ Watching him live in a continuous and uninterrupted kindness and serenity, this man of God, the simple old man, you cried out from your nostrils: ‘It is a good thing to follow the Lord!’

Father Hieronymos lived as an earthly angel, a heavenly man.

Source: Translated by John Sanidopoulos.