When the Athens Acropolis was a village in a castle

New book by restoration expert Fani Mallouchou-Tufano describes monument’s transformation from medieval fortress into archaeological site

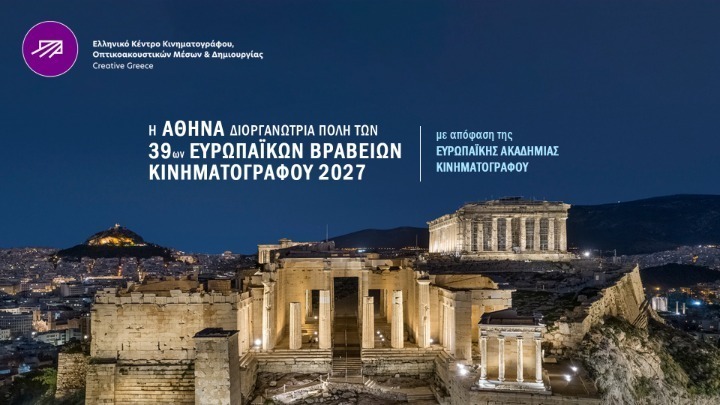

The monuments on the Acropolis of Athens and any work carried out on the Sacred Rock always tend to draw attention. We saw this happening again with the interventions to facilitate wheelchair access, which sparked controversy among experts concerning the impact of this work. Yet the president of the Friends of the Acropolis Society, honorary ambassador George Savvaidis, believes that most of the public, Greek and international, knows very little, if anything, about the Acropolis’ more recent history, from the early 19th century, when the modern Greek state was established, to the present.

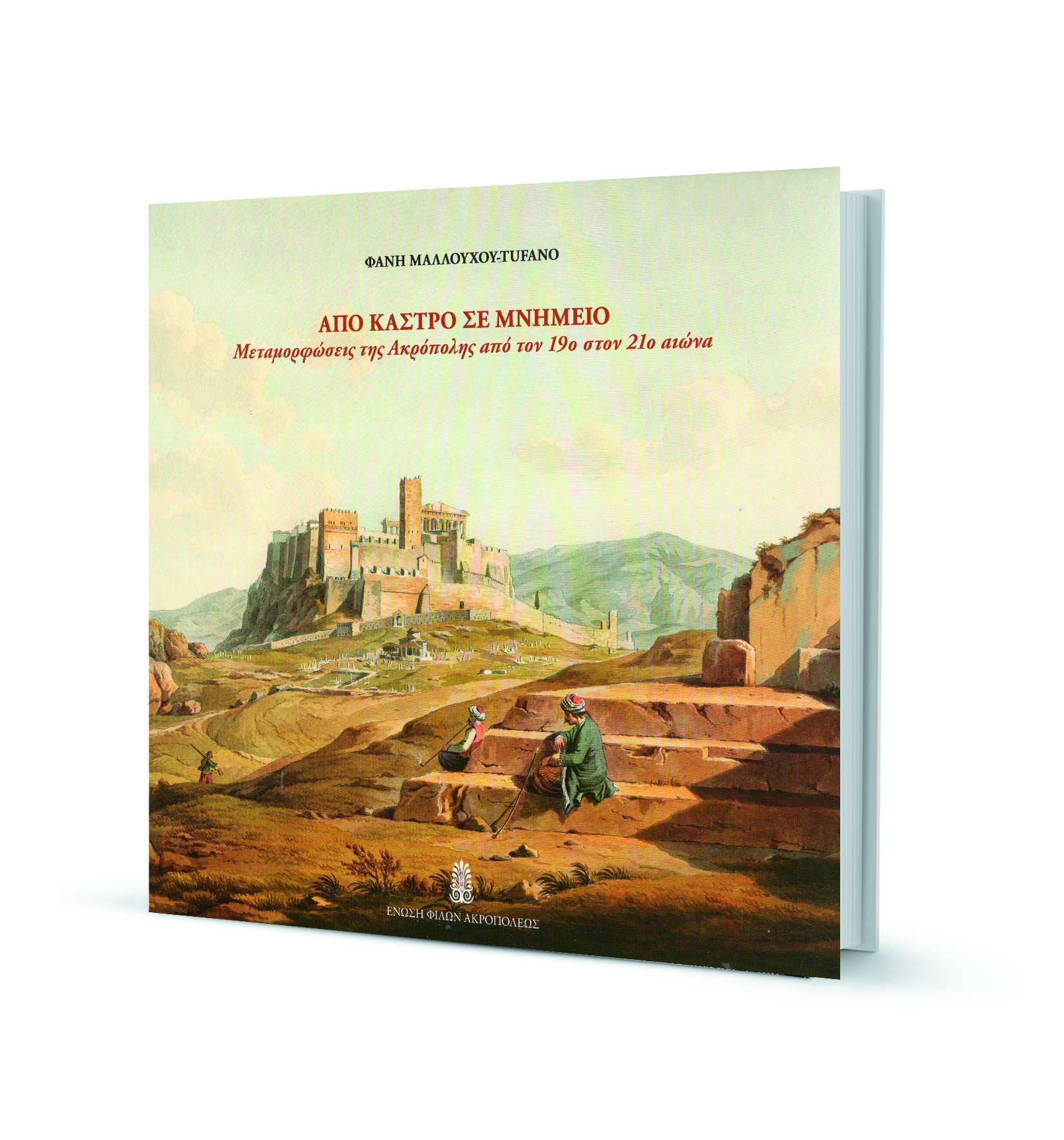

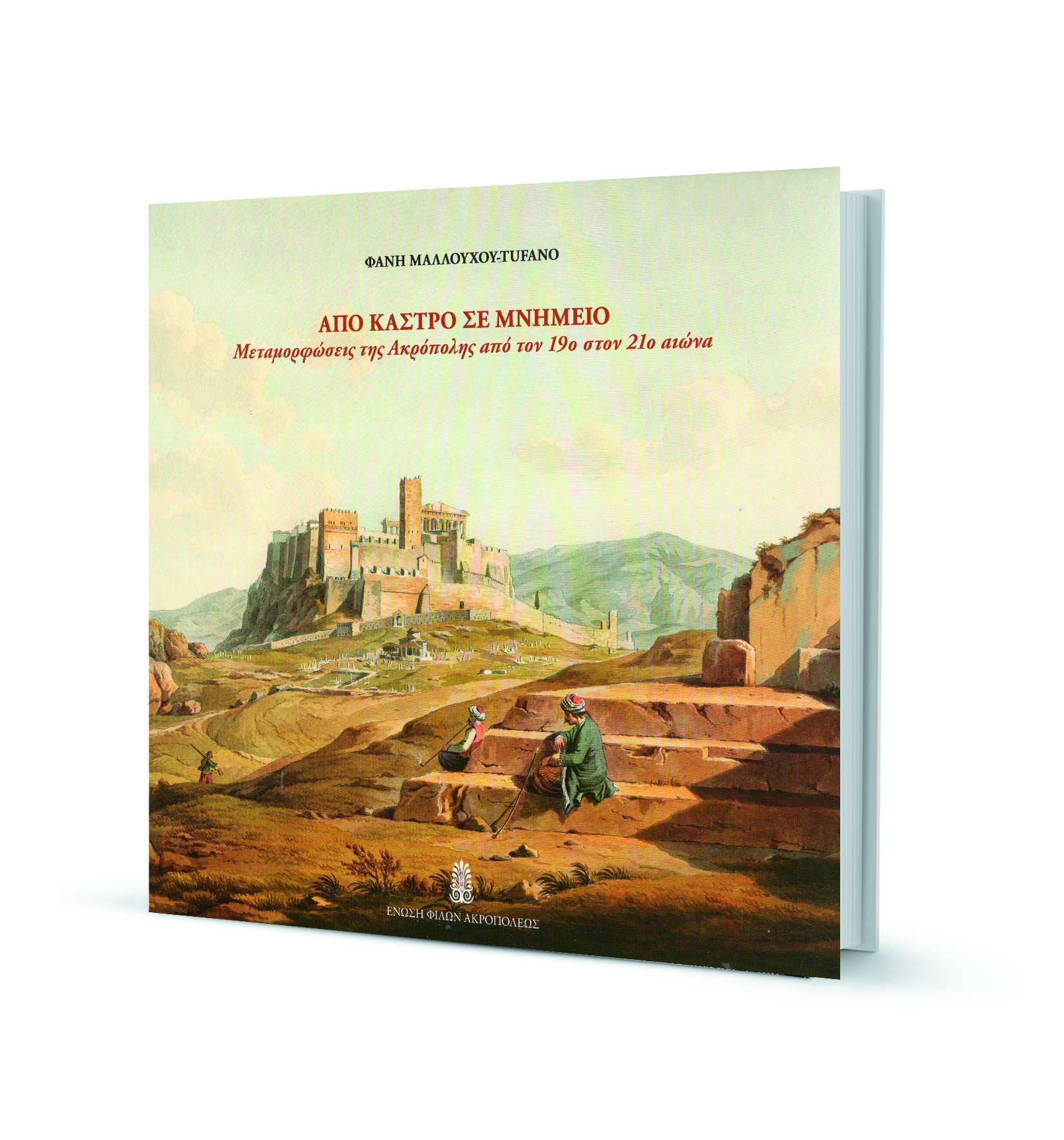

This dearth of public knowledge on the modern history of Greece’s top archaeological site, including restoration work and other interventions that have been carried out, their philosophy and purpose, and the techniques that were applied, is addressed in a new book (in Greek) published by the society. Titled “From Castle to Monument: Transformations of the Acropolis from the 19th to the 21st Century,” the book is written by Fani Mallouchou-Tufano, a Technical University of Crete professor and expert in the restoration of historic monuments. She has also served as the alternate president of the Committee for the Conservation of the Acropolis Monuments (ESMA) since 2016 and is vice president of the Friends of the Acropolis Society.

Speaking to Kathimerini, she says that the idea for the book was sparked by the controversy which erupted three years ago over the installation of wheelchair ramps and pathways on the site.

“Even international media took a position on the issue at the time, denouncing the ‘concreting’ of the monument, because reinforced concrete was used to make the paths. The Ministry of Culture argued that concrete wheelchair paths have existed on the site for the past 20 years, but had been damaged over time by heavy use. It also argued that this was the only way for thousands of visitors with mobility problems to reach the monuments.

Even UNESCO was notified and Culture Minister Lina Mendoni suggested that it send a delegation to check the monuments first-hand. We, the members of ESMA and the Acropolis Restoration Service, showed the three-member UNESCO committee all of the different phases of the work that was carried out on the Acropolis. The briefing actually began with a lecture by me and a PowerPoint presentation on what the Greek state has done to the monuments since 1834. Even these high-ranking members of UNESCO knew nothing about the modern history of the Acropolis,” Mallouchou-Tufano notes.

In 120 pages, the book describes the changes that the site has undergone in the past 200 years, explaining how it was transformed from a castle fortress on the eve of the establishment of the Greek state into an archaeological monument and architype of classical art and architecture.

“A lot was said about the passageways on the Acropolis and ESMA was accused of destroying the medieval ones, but the public should know that they had been removed from the Acropolis since the late 19th century. Indeed, Panagiotis Kavvadias, the ephor general of antiquities, claimed in February 1890 that he was delivering the Acropolis in a ‘cleansed’ state,” says Mallouchou-Tufano, referring to a decision at the time to remove all traces of foreign intervention from the monument and return it to its “original” state.

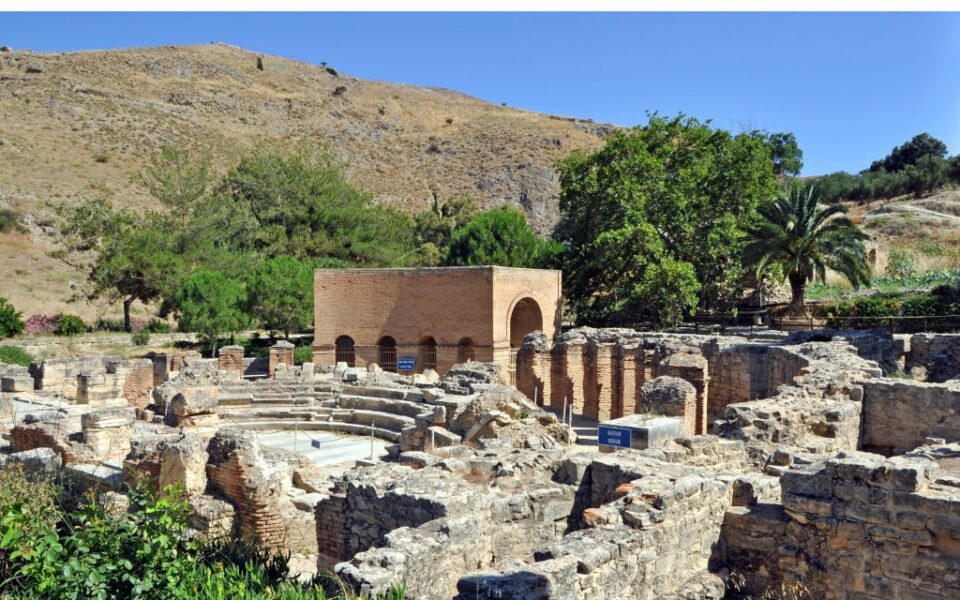

The book is organised into five sections, starting with how the citadel began being transformed into a mighty fortress in the late 3rd century after the city was invaded and plundered by Barbarians in AD 267. The fortifications were significantly strengthened after 1204 and the Frankish (Latin) occupation of Greece and Athens, and again in 1458 after the Ottomans took the city. Among the classical monuments, the inside of the castle contained houses for the people guarding and working in it. It was a proper village, with streets, yards, cisterns, a bathhouse and ammunition depots. A small mosque inside the Parthenon served the residents’ religious customs, while pieces of marble from the 1687 explosion littered the ground around it.

‘Even international media took a position on the issue, denouncing the “concreting” of the monument’

Different phases

The book describes the work of that dedicated rescuer of antiquities, Kyriakos Pittakis, too, but also the restoration carried out by Nikolaos Balanos, who, according to Mallouchou-Tufano, “did not choose the technology himself, but used it and applied it very poorly and carelessly.”

We learn about what happened to the Acropolis after World War II and are given detailed descriptions of the more recent restoration efforts. What is also interesting is the small stories interspersed among the main narrative. Like that about the violent removal of the sculptures by Lord Elgin between 1801 and 1803, describing the damage inflicted on other parts of the monument by falling marble as the decorations were wrenched off from a height of 10 meters.

We see the Acropolis in the throes of the 1821 Greek War of Independence, and when King Otto announced the start of its restoration by banging one of the Parthenon’s columns with a hammer three times, but are also informed of the ongoing pillaging of the monument through the journal of antiquities ephor Panagiotis Efstratiadis (1815-1888).

The book also describes accidents that affected the monument, such as the fire of 1869 that was started by a careless soldier carrying a torch into a guard post containing pyrotechnics that were to be used to light up the monument during a visit by the heir of the British throne.

“Every intervention on the Acropolis has prompted a public reaction,” says Mallouchou-Tufano, pointing to the outcry over the demolition of the Frankish Tower at the Propylaea in 1875. But she also mentions the example of journalist Zacharias Papantoniou, who had opposed the restoration of the north colonnade, not an intrinsic part of the site in the public mind. When it was unveiled on May 17, 1930, he wrote: “I was, I confess, among those who expressed alarm at what the restoration would lead to. But yesterday, after going up to the monument twice and seeing the result in two different lights, in the morning with the sun and in the afternoon with clouds, things changed for me. I saw that an essential piece of work had been carried out. And after strictly weighing what we get from the ruin with what we get from the restoration, I found that the gains from the latter were much greater and more important.”

Likewise, Mallouchou-Tufano believes that the “planned restoration of the western ascent to the Acropolis, with the recovery of the Roman-era staircase, will bring a radical change to the image of the Acropolis’ monumental landscape as it has prevailed in the collective memory and conscience.”

The ticket debate

But what does she think about the most recent controversy, stemming from the government’s decisions to outsource ticketing to a private company, to raise admission prices, and to introduce exclusive tours costing a whopping 5,000 euros?

“These are modern management methods. I don’t like the 5,000-euro tour myself, but even though I was on the Central Archaeological Council, I did not oppose it. This is the spirit of the times,” she says.

And what about the new policy for controlling overcrowding by introducing time slots?

“It is the only solution. The committee has been accused of doing it for the visitors, but no, we are doing it for the monument, and the public benefits too.”

Source: ekathimerini.com