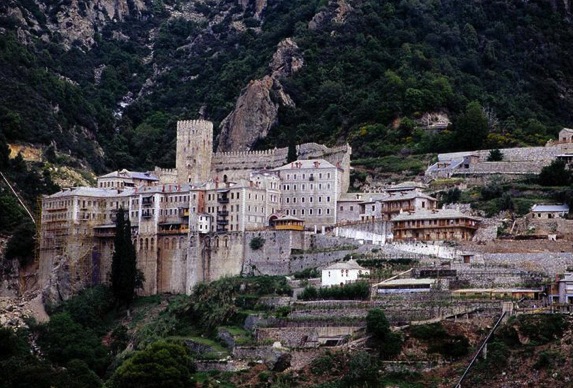

Resistance on the Holy Mountain

During the Occupation [of Greece by the Germans in World War II], Fr. Georgios Ayiopavlitis was a gardener and he was inducted into the Resistance. Together with other monks, he assisted Allied escapees, but was betrayed by a Romanian [For most of WWII, Romania was an ally of Germany].

He was arrested and taken away to the Pavlou Mela barracks [in Thessaloniki], where he appeared before a military tribunal. The judge asked him: ‘Why are you helping the enemy escape to Smyrna and Egypt?’

‘Because they’re in need’, he answered. ‘If somebody knocks on your door, what can you do? In the Gospel, Christ tells us to help those in need of assistance’.

‘So, if a German came to you and asked for assistance, you’d help him?’

‘If he needed it, of course I would. Depending on what his needs were. But you don’t need anything. You’ve choked people with blood. You’ve drenched humanity with blood’.

The tribunal condemned him to death. They took him to the detention center at Eptapyryio [prison in Thessaloniki] and two days later he fell ill with malaria. They took him to the sanatorium, where they were already treating Panteleïmon and Theofylaktos Nanopoulos* (two actual brothers who were monks living in the Kelli of the Typografi [‘Printers’] in Karyes) and old Fr. Meletios Sykiotis [a well-known iconographer who also taught Byzantine music at the Athoniada School on the Holy Mountain].

Fr. Georgios was burning up with fever. One evening, at dusk, he recovered somewhat, sat up in bed and said: ‘I’ve just had a visit from Saint Paul [who founded the Monastery of Ayiou Pavlou, as well as that of Xiropotamou] and Saint George [the main church of Saint Paul’s is dedicated to him] and they told me they’d set me free in three days’.

The others didn’t believe him and assumed he was rambling because of the fever. Fr. Georgios fell back and passed out again.

Three days later, even though he could barely stand on his own two feet from the fever and general exhaustion, at 3 o’clock in the afternoon he jumped from the third floor and landed in a tree- without a scratch- and was able to make his escape. Even though the area was heavily guarded, nobody saw hide nor hair of him.

He set off for the Monastery, the only place where he’d be safe, because outside it there was a danger of being re-arrested. He set out on foot, not really knowing how he was going to get there. When he reached Gomati [a village in Halkidiki], he encountered an informant of the Germans. The man said: ‘I’m suspicious of you. You’re under arrest’. He brandished a pistol and forced Fr. Georgios to walk ahead of him. As they were walking along a narrow path, Fr. Georgios pretended to stumble, turned quickly and wrested the pistol from his captor.

The man entreated him: ‘Spare me. I’ve got a wife and child’.

Fr. Georgios did, indeed, spare the man’s life and continued on towards the Holy Mountain. But he hung on to the ‘iron’ as he called the pistol. At Monoxylitis [a wine-growing area at the border of the Holy Mountain], he was almost recognized by a worker from one of the neighboring villages but he talked his way out of it and reached the Monastery. He didn’t go straight in, though. He went to live in a cave above the Monastery and the only people who knew he was there were Abbot Serafeim, Papa-Andreas the refectioner, and Fr. David.

On Saturdays, when he celebrated the Divine Liturgy in the cemetery church, Papa-Andreas would take Fr. Georgios Holy Communion in secret. They would meet at another cave, that of Saint Paul himself, which is a little further up, beyond the monastery’s tower. He lived for 19 months in the cave, including through a very harsh winter. He invented a number of ruses. He used to light the fire at night, so that the smoke wouldn’t be visible, but the cave would be warmed. Also at night, he received food in a basket which they let down over the walls.

In spring, because the sun came round late, he’d go out and sit on a rock. On one occasion, he was bitten by an adder, but he called upon Saint Paul the Apostle and was unharmed [cf. Acts 28, 5].

One day he saw three monks on the path leading to Karyes, one of whom was the person who’d betrayed him. He still had the pistol with him and could have taken his revenge but he allowed them to go on their way.

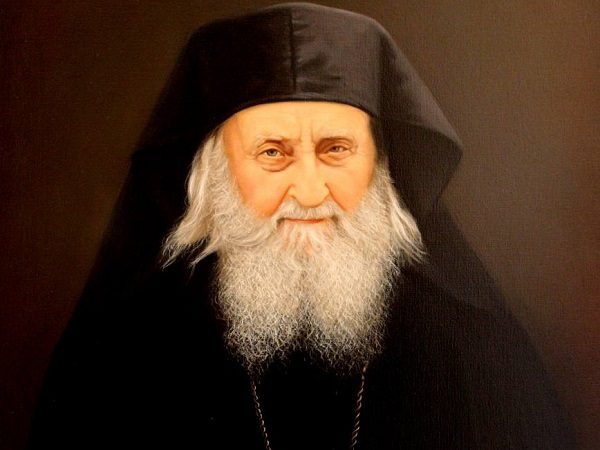

The Germans decided to burn down the Monastery because they suspected that Moskhonas (Fr. Georgios] was hiding there. They made a mistake, however, and went instead to the Monastery of Dionysiou, which lies just before Saint Paul’s. They gave the monks a deadline of a week to gather their things and leave. When they realized their mistake, Abbot Gavriil of Dionysiou delayed their departure while he sent word to Saint Paul’s that the Germans were coming. The monks then understood why Papa-Sophrony [now the newly canonized Saint Sophrony from Essex, who was then the spiritual father of the Monastery] had told them the previous day to go to their cells and pray, because a disaster was about the befall the monastery.

With the help of the secretary, Fr. Theodosios, the monks prepared a supposed condemnation of Fr. Georgios, including a resolution to hand him over themselves, when they saw him. The Germans arrived, were shown the document and the monastery was saved.

When the Occupation ended and the danger was over, Fr. Georgios went back to the Monastery and resumed his duties.

He said: ‘I went through a lot, but I’ve never felt such rapture of the soul. It was a blessing from Saint Paul and Saint George, who set me free’.

Source: Από την ασκητική και ησυχαστική Αγιορειτική Παράδοση, chap. 24, “Γερω-Γεώργιος Αγιοπαυλίτης” The Holy Mountain 2011.

* These two were later to have a remarkable escape from death themselves. Father Theofylaktos told the story later:

The Kelli of Saint Nicholas (Typografon) where the two brothers lived

‘During the German Occupation, they arrested me and my brother after the flesh, Papa-Panteleïmon, and sent us to Dachau. One night, they took us out to execute us. It was winter and they stripped us naked. We waited our turn. We had no hope of being spared. Then I remembered the Holy Forty Martyrs [to whom the main church of the Monastery of Xiropotamou, the other monastery founded by Saint Paul, is dedicated] and said: “Hey, Panteleïmon. What’s the dismissal hymn for the Forty Martyrs? Do you remember it?” And he began to sing, in tone 1:

“Be moved, Lord, by the throes which your saints suffered for you, and, we beseech you, of your love for us, heal all our pains”.

Immediately a warmth spread around us both and we didn’t feel the cold. It was the presence of the saints, who had also suffered from freezing.

The night passed and in the morning we were expecting death, but an order came through saying that we two monks were not to be executed. Of all those who were sent there, no-one else escaped. This is why our names were later written on a plaque which was placed at the death camp’. [WJL].

Source: Από την ασκητική και ησυχαστική Αγιορετική Παράδοση, part 2, chap. 13, p. 344. The Holy Mountain 2011.