86th TIF: Exhibition marks centenary of the Asia Minor Disaster of 1922

Visitors to the 86th Thessaloniki International Fair (TIF) will have the opportunity to learn about one of the darkest moments in Greek history, the Asia Minor Disaster of 1922, in an exhibition set up to mark the centenary since the events unfolded.

The exhibition “AEON… in Ionia, Thrace and Pontus” will take them on an audiovisual journey that spans moments in the lives of ethnic Greeks living in present-day Turkey before the forced exchange of populations, the refugees’ flight from Asia Minor, Thrace and Pontus to Greece, how they settled in Greece and became incorporated into the Greek state.

Deputy Professor of Modern Balkan History of the University of Macedonia, Dr. Vlasis Vlasidis, who was responsible for collecting the archival material and the historical accuracy of the exhibition, stressed in statements to the Athens-Macedonian News Agency that this tribute, which features an original score by Yiannos Aiolou and edited by N-CODE EPE Audiovisual Productions, highlights the positive impact of installing the refugees in Greece.

From premodernity to modernity

The audiovisual presentation will be housed in Pavilion 6, in an area of 500 square metres, and will show how these populations passed from premodernity to modernity, leaving behind a tranquil, traditional way of life and finding themselves forced to follow orders, to leave, board ships and go into quarantine.

“From each person being responsible for themselves, they suddenly enter an organised society and for the first time obey orders for their own good, in order to save themselves,” Vlasidis said.

Mental collapse in the refugee boats and the controversial quarantines

Very little material has been found regarding life on board the ships in the four- to eight-day journey from the Turkish shore to Thessaloniki, Kavala, Makronissos and Piraeus but this part of the story has been included in the narrative, as it had a profound impact on the refugees emotionally.

“We will try to decipher it, even though it is very difficult, as it does not only have to do with the real conditions of the trip but also the fact that the refugees, who had lost everything in their lives, underwent a mental collapse once they were on board the ships and felt safe,” Vlasidis said.

While much has been written about the quarantines and decontamination centres once the refugees reached Greece, and the appalling conditions in which they lived there, Vlasidis noted that even though the refugees perceived this as punitive, there were actually a great many infectious diseases and many people had died. “If they had left this unchecked, it would have been a very great disaster for the local population as well,” he added.

Creation of a middle class and separation of memory and fact

The state preferred to install the refugee populations in the countryside and not in urban areas, and therefore allotted parcels of land which, depending on the area and the number of children in each family, could reach up to 3 hectares, including a house, livestock and tools to get started.

“The state at the end of the 1920s and early ’30s would greatly assist the refugees settle in and help to create a middle class, not a cheap and destitute workforce,” Vlasidis said, adding that the Greek government saw the refugees as a lever for improving things.

“At that time, the state also truly changed, itself graduating to modernity. We then had very great changes in many areas, such as the provision of free education to all, the creation of hospitals by the state, ports, the draining of land and road networks. Projects carried out in the ’60s and ’70s had been initiated then. They were not only for the refugees but the role of the refugees was a catalyst and the state was used for the good of society,” the professor noted.

“The memory of refugees is focused on drama, destruction, abandonment. It looks at those that were lost and not those that were saved. The installation at the 86th TIF strives to show the narrative of the refugees about what truly happened to them but also the importance of what was done by the Greek state and how successful this effort was, overall,” Vlasidis pointed out, underlining that the experiences were a different issue to the event in its entirety.

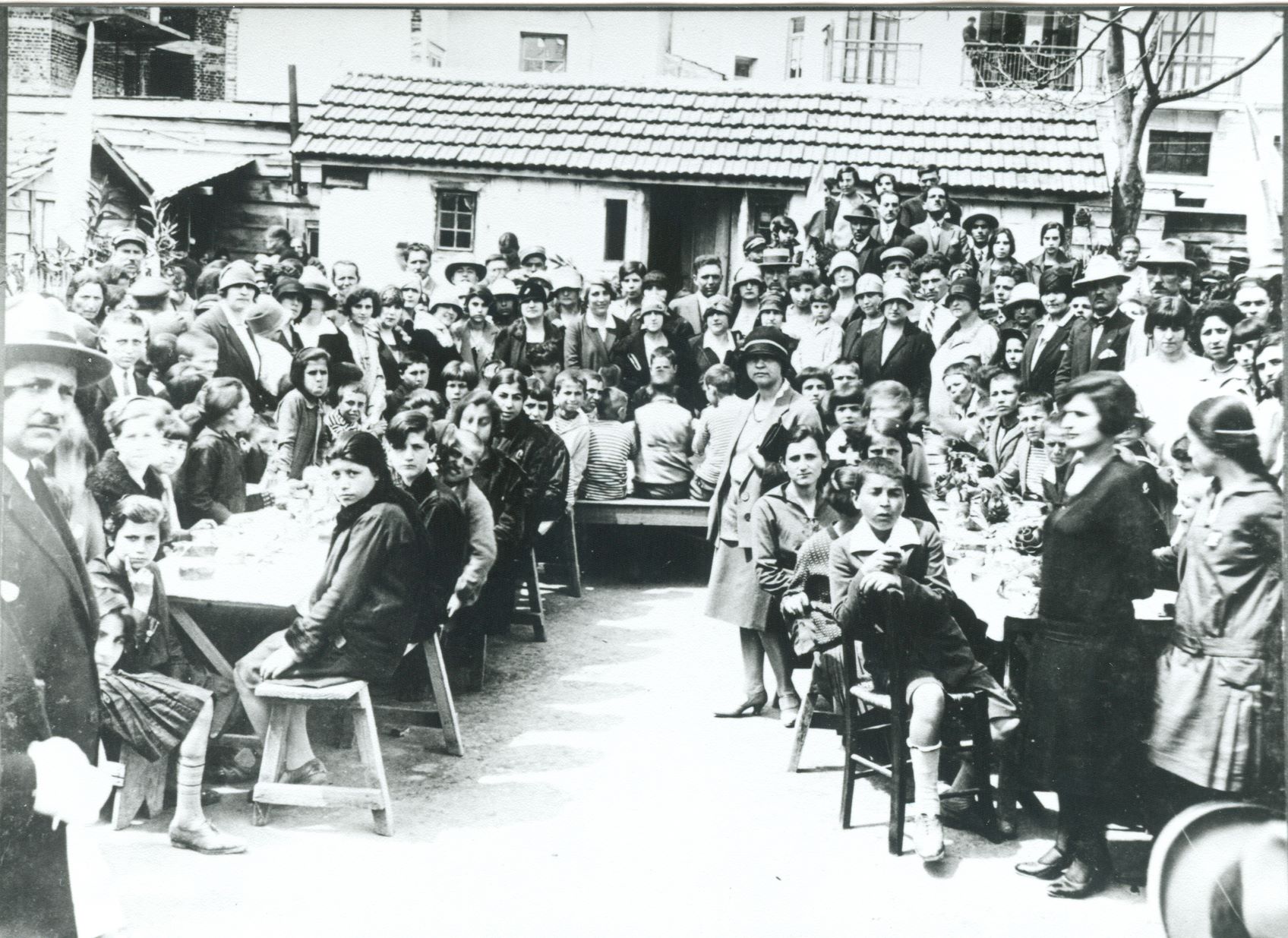

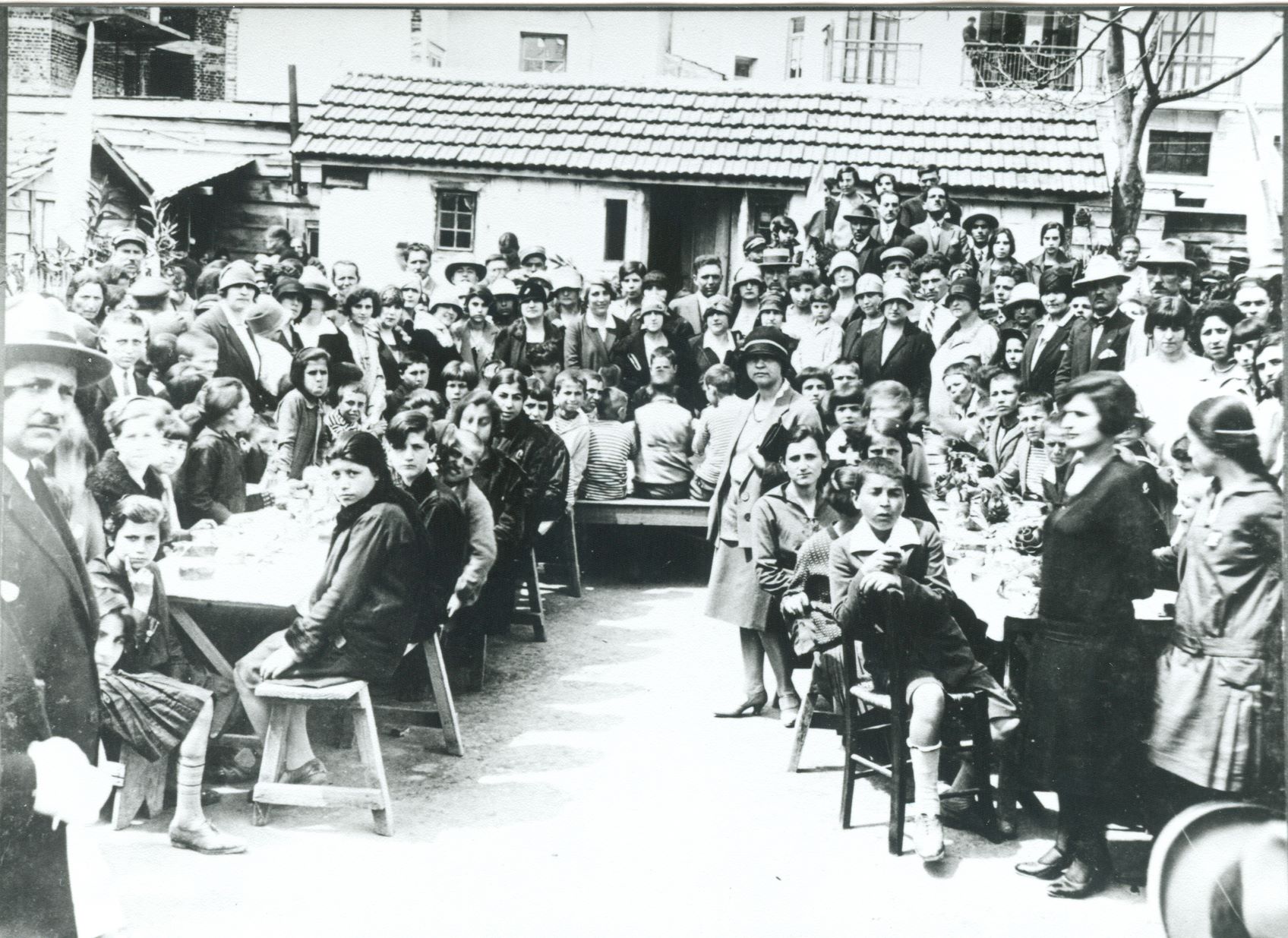

The photographs above were supplied by Dr. Vlasidis from the Historical Archive of the Refugee Greeks of Kalamaria – Smyrneans’ Union – Thracian Home of Katerini. They depict the Greek community hospital, burnt and destroyed, Smyrna in flames in August 1922, a soup kitchen in Thessaloniki after 1922 and the new refugee housing built by the state in Kalamaria.

Source: amna.gr