Pocket satellites made in Greece

So far, so good. It is dawn on September 3 and the members of the Libre Space Foundation are staying up to watch a live broadcast from California of a rocket launch by the private American corporation Firefly Aerospace from their lab in Athens or their homes all over Greece. It is its maiden voyage, anything can happen. The rocket passes the point of maximum aerodynamic pressures, it is now supersonic. Everything is going well. It looks like it will carry out its mission – reaching an altitude of 300 kilometers above the Earth and successfully sending the pocket satellites it has on board, including two manufactured in Greece, into low orbit.

It became known later that one of the thrusters of the Firefly Alpha rocket underperformed for approximately 15 seconds during the flight. “When you hear the countdown and you then see the ignition of the thrusters and the rocket departing with your construction in it, there are jitters. This time there was more stress, because we knew the rocket was riskier,” said Pierros Papadeas, managing director of LSF.

“It was this specific rocket’s first attempt to enter into orbit, and while it had passed static trials on the ground, it is something that can happen. It is difficult to live through, but as we often view launches we know it is part of the process and we can say, ‘Its OK, on to the next one.’” Their work rate has not decreased. They are already constructing four new picosatellites (pocket-sized satellites, weighing approximately 250 grams and roughly resembling a Rubik’s Cube in shape and size) in Athens for their next voyage.

The nonprofit organization Libre Space Foundation was founded in 2015. It designs and develops space technology with the use of open software and has a lab in the center of Athens, in the hackerspace.gr community space. The team’s base core comprises mechanical engineers, electrical engineers, software designers and physicists, who are surrounded and supported by a team of volunteers. Completion of an academic course of study is not a requirement. In collaboration with the University of Patra, they had constructed UPSat, the first open design and open software microsatellite, which successfully went into orbit in 2017, participating in an international program on expanding the thermosphere. After 16 months, it had completed its mission and burnt up upon re-entry to the atmosphere over the Pacific Ocean.

In August 2019, the Spanish company Fossa Systems asked for their collaboration, as they had secured a free spot on the Firefly rocket that would place its own satellites in orbit. It was the first launch attempt for Firefly and for that reason the American company had issued an open invitation to universities, research institutes and others who were in search of a space vehicle. In their lab in Athens, the LSF members worked ferventlyto respond to the tight five-month deadline. They constructed PicoBus, a metal box that integrates with the rocket. This box fits up to eight picosatellites to be released into space.

At the same time they constructed Qubik-1 and Qubik-2, two open software picosatellites, whose objective is to identify satellites as soon as possible after deployment. Another four picosatellites were integrated into PicoBus, Genesis-L and Genesis-N of Spanish AMSAT-EA and FossaSAT-1 and FossaSAT-2 of Fossa Systems.

Manufacturing

Despite the very small timeframe available to them for preparation, the positive thing was that this period did not coincide with the pandemic. They had managed to complete the manufacturing and the trials before the first case of Covid was recorded in Greece – or they would have had to face additional difficulties. “We manufactured the picosatellites with materials freely available on the market. The processors are similar to those found in drones, which you can get cheaply at an electronics store. The two batteries in every satellite are like those used in cameras,” says Papamatthaiou. He estimates that the cost of the materials used did not exceed 500 euros, without counting the work hours, necessary travel, and the cost of the services used to test the durability of their creations.

One of the necessary stages of their venture was to test the full operation of their satellites. “We had to test various scenarios and try various potential errors to see how they could be handled, whether by the satellite or by us on the ground,” says Papadeas. “Physical tests followed. Tests for vibrations and shocks, which they would undergo on the rocket itself, in machines that simulate the launch conditions.”

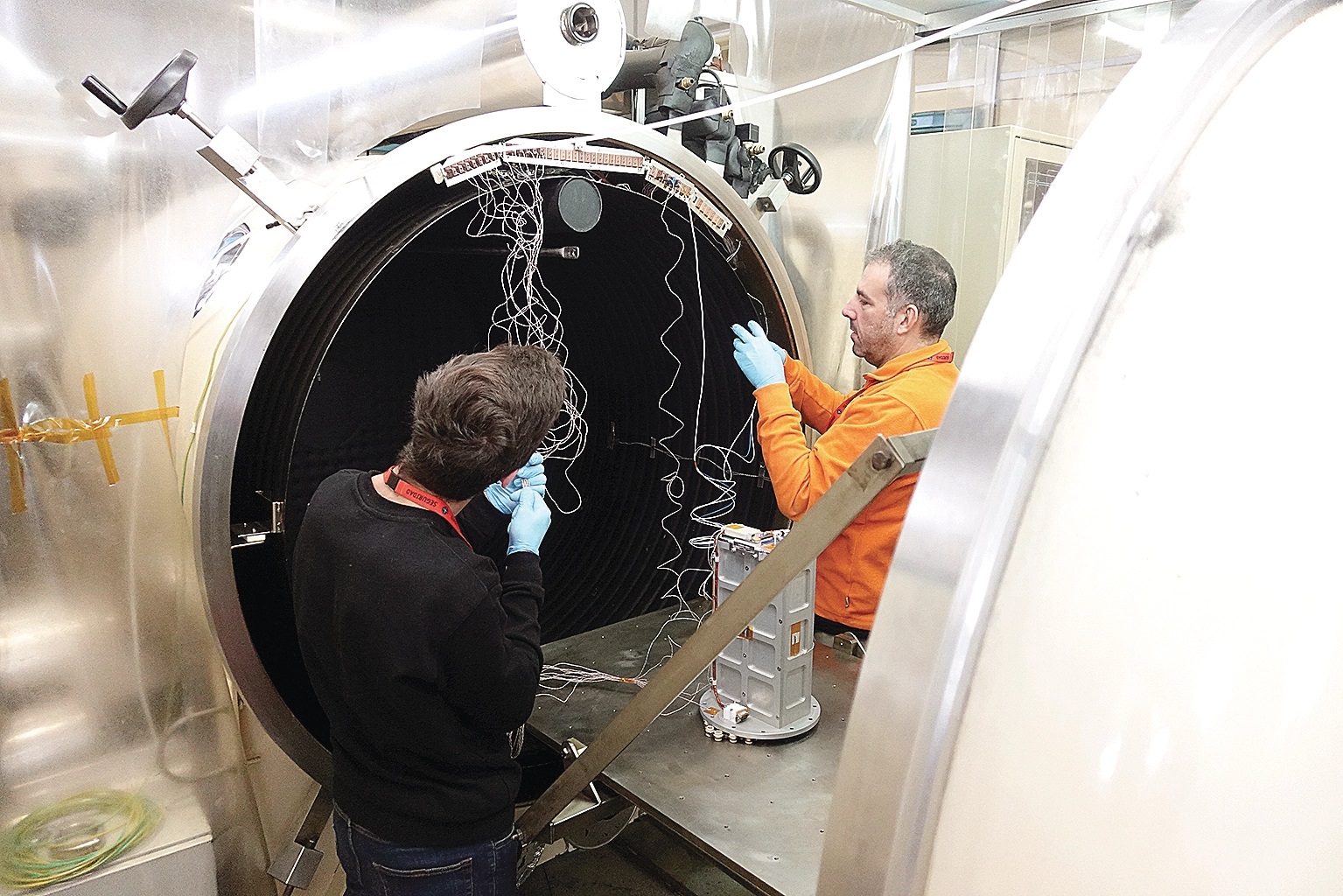

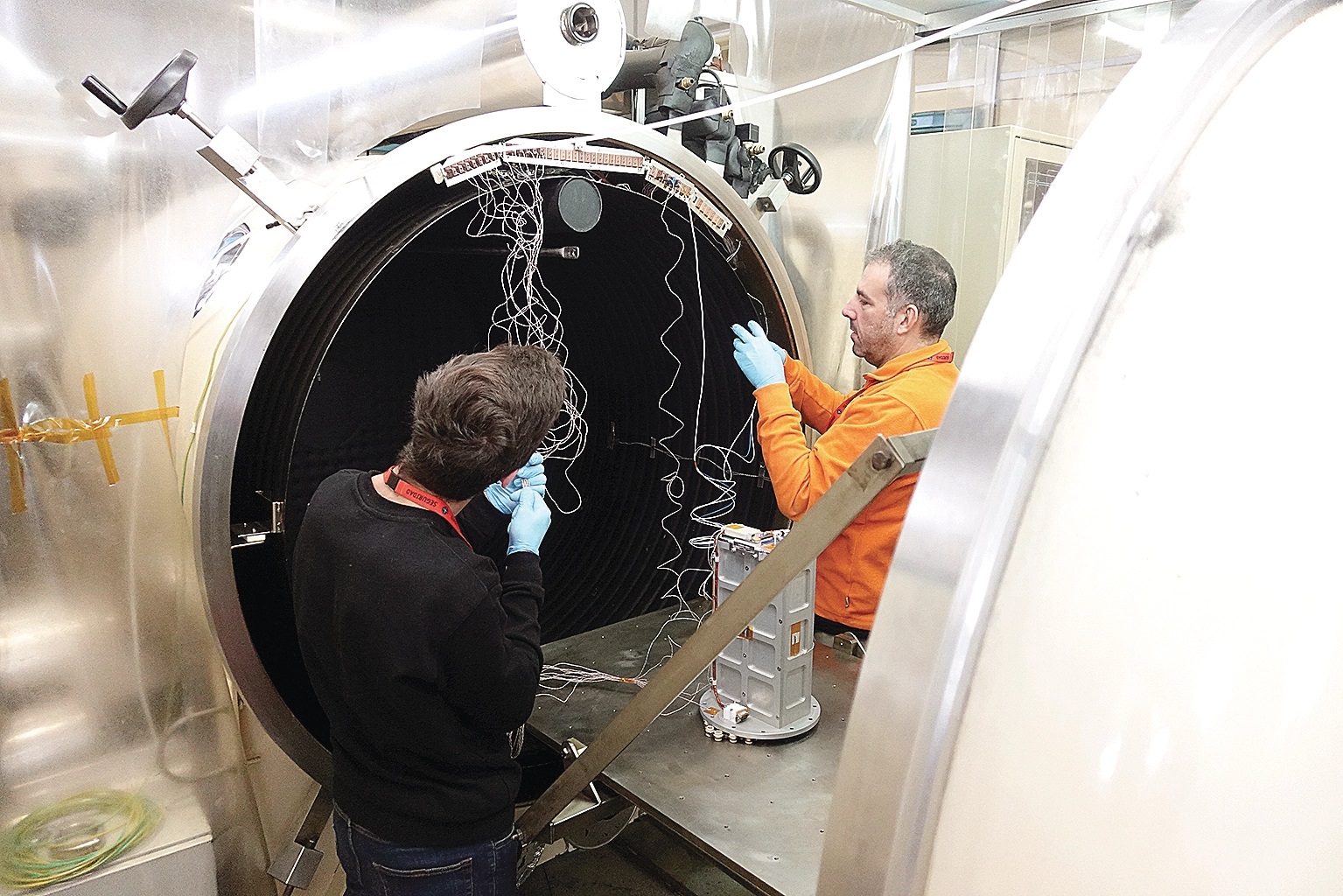

Another stage was placing them in a vacuum chamber with a changes in temperature, to test the durability of the material in conditions similar to those it would face in orbit around Earth. These tests took place in specialist facilities in Spain and at the Foundation for Research and Technology (FORTH) on Crete. “We had to establish that nothing would break during the launch process, so that we wouldn’t put the rest of the cargo in danger,” said Papamatthaiou.

The global future

When Firefly entered into orbit it was supposed to activate the PicoBus, which would release the picosatellites within. Thirty minutes of radio silence would follow while the satellites distanced themselves from the rocket, and then they would begin transmitting signals back to Earth. Their outer shell had photovoltaic panels and, in the interior, the satellites had subsystems tasked with different functions, such as energy management or communication with ground stations.

The two picosatellites would have three weeks available to complete their experiment. The team members would try various types of signal broadcast to trace satellites. “It is important for space safety. As the number of satellites multiplies, there is a greater need to know where they are in order to avoid collisions,” says Papamatthaiou.

The Qubik picosatellite experiment would be supported by a network of 350 terrestrial satellite stations (SatNOGS), that had already been developed during a previous venture by the Libre Space Foundation. “It is an experiment that is taking place in the framework of an amateur radio service. A section of the radio spectrum has been given to radio amateurs for research and the development of technology in relation to radio communications and we are taking advantage of that part to develop this technology and make it accessible for everyone,” says Papadeas.

Recently, in collaboration with FORTH, they have undertaken the SIDLOC (Spacecraft Identification and Localization) project, which is funded by the European Space Agency. The basic aim of this venture is also to trace satellites in space and to solve issues of congestion. They are going to plan and develop an independent radio lighthouse, a device with solar panels that will focus on radio beacons to facilitate their rapid identification on Earth and reveal their location and orbit at anytime.

Transmitting information

Over the last few decades, access to space has expanded beyond the strict confines and bipolar system established during the Cold War. The path for private enterprise and ventures has been paved. “More countries are designing rockets capable of entering into orbit and more companies in various countries are participating in this process. The costs of building a satellite, launching it, and the technology used to communicate with it are all coming down,” states Papadeas. “This reduction of cost and this variety of available choices on how to reach space, whether by sending an item or even a human being in some cases, help toward the wider acceptance and use of space technology.”

He also notes a parallel trend that is being seen internationally in the aerospace sector, which their team represents. Their organization supports the free sharing of information through open source code and software that are exchanged on the internet at no cost, free of intellectual property rights. “We believe that everything should be done with the purpose of spreading knowledge and the peaceful use of space, to broaden humanity’s horizons,” concludes Papamatthaiou.

Source: ekathimerini.com