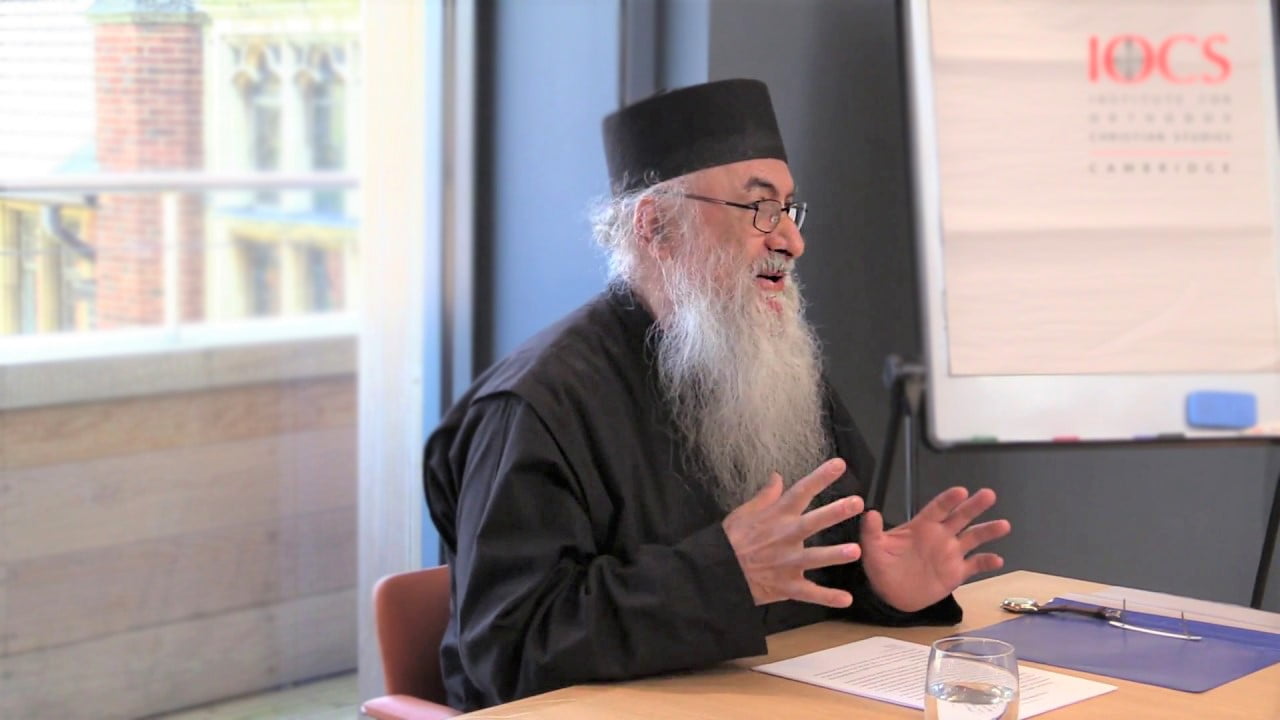

On Conscience (Rom. 2:10-18)

By Archimandrite Zacharias Zacharou

The apostolic reading (2nd Sunday of Matthew) speaks about the theme of judgment and conscience.

Our God is a God that ‘trieth the hearts and reins’.[1] The day of Judgment will come as a surprise because the Lord will judge the hidden intents of the heart. The judgment will not be the same for all. According to the word of the Lord, those to whom much is given, from them much will be required.[2] And the Apostle confirms: ‘For as many as have sinned without law shall also perish without law: and as many as have sinned in the law shall be judged by the law.’[3] In other words, divine grace is an honour but at the same time a cross, because it entails judgment. Those who receive it ought to prove themselves faithful in keeping the sacred trust which the Lord has committed unto them.

The Apostle Paul observes that there were heathens who, without knowing God’s ordinances for the Jews, were doing good because they had the divine law naturally inscribed in their heart. And Saint John Chrysostom begins his commentary on Saint Matthew’s Gospel by saying that, a man who keeps a good conscience and purity of heart and mind, no longer requires Holy Scripture because the Spirit of God engraves the divine law directly upon his heart.[4] Before Moses received the Law, this is what happened to the Righteous of the Old Testament. They were well-pleasing to God because His counsels were imprinted in their conscience and they obeyed them.

What, then, is our conscience?

Man was formed by God’s holy hands and received in his nostrils His life-giving Breath. This reveals that God had an especial and direct concern for His reasonable creature. In Paradise, man delighted in the vision of God. He had no need for the written divine word, because God set forth Himself before him as an example to be emulated.

God fashioned man in His image and likeness and planted within him a fervent and luminous vision, a spark, that would dictate to him that which was pleasing and that which was abhorrent to his Creator, giving him the insight to discern his thoughts and follow the path of God’s will. This luminous vision is called the ‘conscience’ or the ‘natural law’.[5] However, through our disobedience and fall into sin, this spark was extinguished, or rather, it was buried beneath the mud of the passions.

It can be established, therefore, that the conscience is innate to man ever since his creation. It is also evident, however, that it is not something static. It can be blunted or refined depending on man’s manner of life.

Our conscience is blunted above all by sin. The voice of our conscience grows faint. Sin covers the light of our conscience and slowly smothers it. When we disobey its voice, our conscience is deadened. Evil often begins with carelessness in little things. This regression, however, blurs the mind and weighs down the heart with inertia. Gradually, man becomes negligent in more serious things, and from small transgressions, he falls into grievous sins, until his mind is darkened and led to destruction.

Our conscience is also blunted when we are immersed in daily cares, when our life is spent in the turmoil of earthly concerns. For this reason, those who are consumed by the longing to draw nigh to God, reduce their needs and cares to a minimum, so that they may cultivate and illumine their inner spark and savour the light of their inner life.

When we disdain our conscience and accept thoughts that come from the enemy, we come into contact with his devastating energy. By contrast, when we heed with close attention to the urging of our conscience and strive to snatch every wave of the Spirit, we keep in continual contact with the energy of God that cleanses, saves and sanctifies.

If man does not repent, his little falls lead to greater falls. However, the opposite also applies. If he is diligent for his conscience sake in small and seemingly insignificant matters, his psyche, his nature and his will are strengthened so that he can take on greater spiritual works. For example, perhaps we do not all have the endurance to keep all-night vigils. Let us pray according to our strength for one hour, half an hour, be it only for ten minutes, but let us not neglect prayer altogether. If we persist in steadfastly carrying out a much as lies in our power, our soul will acquire more and more strength and light. Our honest and humble struggle attracts grace to collaborate with us until we derive so much joy from our converse with Christ that we are distracted neither by time nor our bodily fatigue.

When the light of our conscience starts to flicker out, man must labour hard in the keeping of the commandments to quicken the flame. For his conscience to be healed and restored, man must feel pain, fear and shame. Pain is the beginning of humility, fear is the beginning of love and shame the beginning of repentance.

The energy of grace and every word that comes from God work upon the conscience and refine it, and man thus becomes ‘taught of God’. Discerning the thoughts that approach man’s mind, that is, understanding from where they originate, is of vital importance.

There are three kinds of thoughts. Firstly, the thoughts that come from God, which inspire us, refine our conscience, illumine our mind, warm our heart, regenerate us and draw us closer to the Lord. Secondly, the natural thoughts, which are neutral. For example, when we are hungry, the thought comes to our mind that we must eat; when we are tired, that we should sleep and so on. Thirdly, there are demonic thoughts which come from the enemy and lead to perdition. Such thoughts must be repulsed immediately by prayer.

One reason that transcendental meditation is dangerous for the spiritual life is that when a man practices it, he tries to divest himself of every thought. Consequently, he suppresses the voice of his conscience. By denying each and every thought, he rejects even the thoughts that come from God and repels the workings of grace. He closes the ears of his soul to the voice of the Lord, and thus ceases to live a prophetic life.

In the Gospel, the Lord refers to the theme of the conscience in a very figurative way. ‘Agree with thine adversary quickly, while thou art in the way with him; lest at any time the adversary deliver thee to the judge, and the judge deliver thee to the officer, and thou be cast into prison. Verily I say unto thee, Thou shalt by no means come out thence, till thou hast paid the uttermost farthing.’[6]

The adversary ‘in the way’ is the conscience, a fellow traveler that man must be reconciled to as long as he journeys the path of this life. For the man who lives with negligence and is not at peace with his conscience, however, it becomes his implacable judge for all eternity. The voice of his conscience which he suppressed in this life, becomes a loud cry, ‘Woe is me!’ before the Countenance of the Lord Jesus on the day of His Coming. St Andrew of Crete confirms that, ‘There is nothing in the world more violent than our conscience.’

The Fathers state that we should tend to our conscience on three levels: towards God, towards our neighbour and towards the created world.

Our conscience toward God is secret. This is why in today’s reading, the Apostle says that God will judge ‘the secrets of men’.[7] That which will justify us or condemn us on the day of judgment will be our hidden inner content, our thoughts, our intentions, the movements of our heart, the feelings that we take pleasure in.

The content of our heart is revealed above all both in the quantity of prayer and, even more, in its quality. That is, our heart is revealed by the time that we dedicate to our converse with God, by the humility of the words of our prayer, and by our gratitude and love for the Lord.

Our conscience towards God is revealed in prayer, but it is also preserved by prayer. When we accept evil thoughts, we grieve the Spirit of God and are alienated from Him. By contrast, if through prayer we reject the suggestions of the enemy and ‘bring into captivity every thought to the obedience of Christ’,[8] we prove our love for the Lord and our determination that ‘for the word of His lips we shall keep hard paths’.[9]

We preserve our conscience towards our neighbour when we are careful not to grieve our fellow with any act, word, movement, glance or thought; when we avoid laying any stumbling block before our neighbour or provoking his conscience. Our presence must be humble and not usurp the spiritual space with spectacular manifestations of feigned piety. When we speak about our fellows our word should always exceed the measure of their virtue and in whatever we do, say or think about them, we should add a portion of love. If we keep this rule, at the end we will inherit the grandiose portion of divine love.

Finally, we preserve our conscience towards our environment when we do not behave as owners, but as priests of creation. That is, when we make sparing and careful use of material goods for our needs, in reverence and awe, without greed and abuse, but above all offering up prayers of thanksgiving to God. Then all creation is blessed, because ‘every creature of God is good, and nothing to be refused, if it be received with thanksgiving: For it is sanctified by the word of God and prayer.’[10] It is evident that if we had each kept a good conscience towards the created world, we would not be faced with the devastating environmental crisis that now threatens the life of all on earth.

Of course, a good conscience towards our neighbour and towards creation stems from a good conscience towards God. When man keeps these three kinds of conscience, living in harmony with God, with his fellow and with the created world around him, he begins to fulfil the primordial purpose that God set forth for man: to be king and priest of all creation, and to present it before God with thanksgiving and supplication.

[1]. See Ps. 7:10; Jer. 17:10.

[2]. Cf. Luke 12:47-48.

[3]. Rom. 2:12.

[4]. Cf. St John Chrysostom, Homilies on the Gospel of Matthew, A Select Library of Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers of the Christian Church, trans. Philipp Schaff and Henry Wace, (Michigan: WM. B. Eerdmans, 1956), Homily 1, p. 1.

[5]. Cf. Rom. 2:14.

[6]. Matt. 5:25-26.

[7]. Rom. 2:16.

[8]. See 2 Cor. 10:5.

[9]. See Ps. 16:4.

[10]. 1 Tim. 4:4-5.

Source: pemptousia.com